Casual anthropic principles

Convenience-sampling lived human experience

February 15, 2020 — October 28, 2022

Suspiciously similar content

The first example of an anthropic principle I heard of is the one from cosmology, where we wonder why the configuration of the universe seems to be hospitable to life. But if there is a multiverse, and it is mostly inhospitable to life, would we notice that general inhospitability? Life would only be here to notice in the universes which are hospitable to life, and that is where we are. Those other dead universes devoid of noticing agents might be just as cosmologically common, but essentially irrelevant. There is a lot of philosophical work being done in analysing these large-scale anthropic principles. I should probably handball everything to Nick Bostrom.

Anthropic principles in the sense I mean do not need to be so cosmic. In some systems, the fact that we are likely, or even able, to make observations of those systems, says something significant about which (part of the) system we observe. Put another way, the sampling process that produces us observers is important in constraining the types of observations we are likely to make. In fact, if we do put it that way, then this idea is nothing but a standard idea in statistics. It is an idea that we seem to forget fairly often.

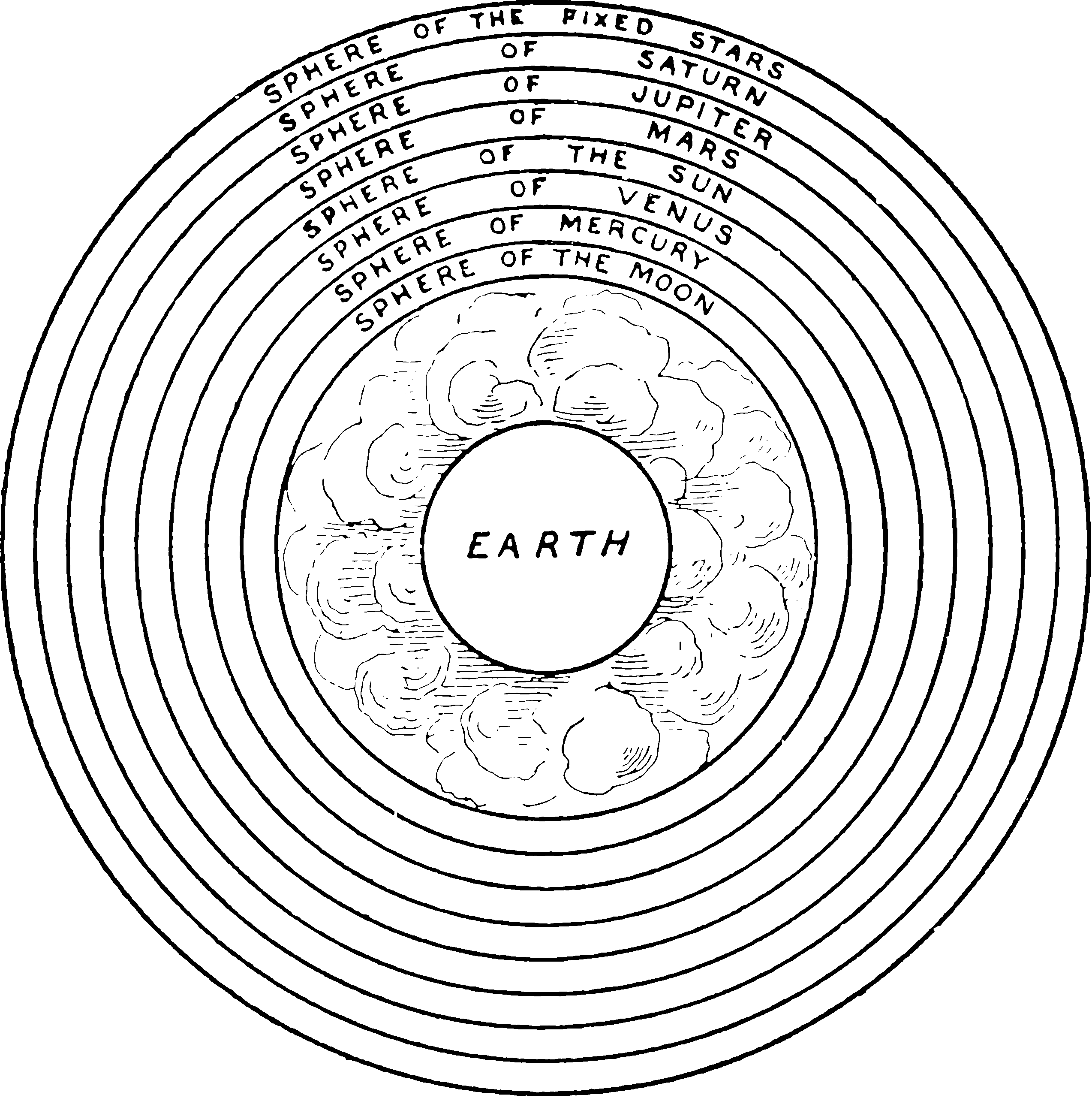

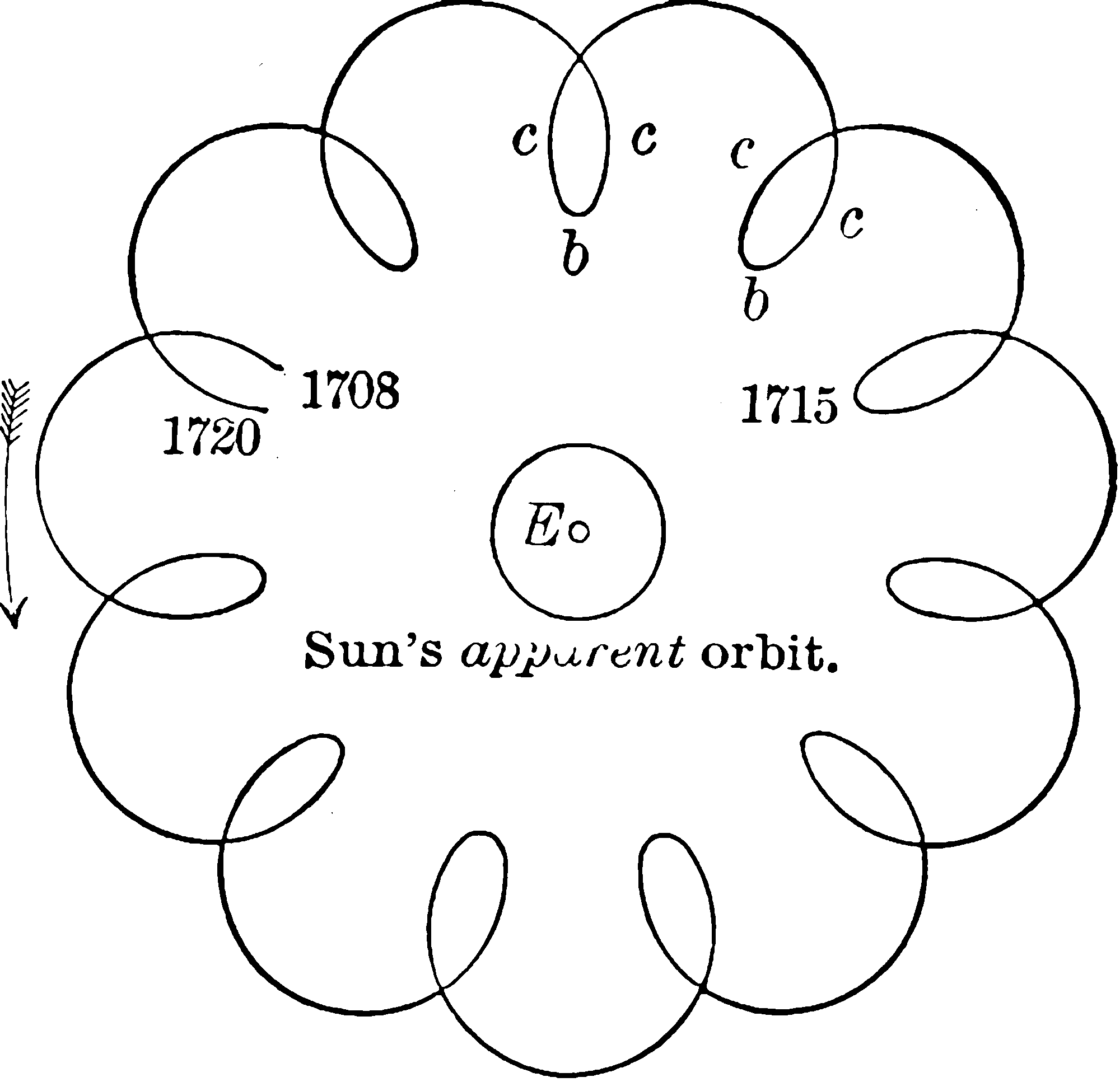

Alternative name for this kind of observational bias problem, also from physics: geocentric models. Before Copernicus, it was frequent and natural to regard the earth as the centre of the universe because certainly all the people who cared about it seemed to be on the earth. This was the geocentric perspective. We have leveraged various evidence since then to understand that possibly our viewpoint might be typical from the perspective of humans, but from the perspective of all the mass in the universe, not so much. When we admit that the earth might orbit the sun, that is a heliocentric perspective.

We are all naturally geocentric instinctually, I think. Naturally, I assume that my perspective is typical unless I have something to tell me otherwise.

On this page is a collection of systems that have anthropic observational bias baked in, and some thoughts for reasoning about this.

It turns out, of course, that I am not the only person to have become curious about this: See, e.g. Katja Grace’s Anthropic principles page Nick Bostrom’s Anthropic Bias for a published book on this theme. There are many small variations. If you want to get philosophical try the sleeping beauty problem.

1 Any statistical analysis is of a problem of a certain degree of fuzziness.

The anthropic principle in statistics. Ken Rice said

Re: the anthropic idea, that (I think) statisticians never see really large effects relative to standard errors, because problems involving them are too easy to require a statistician, this sounds a lot like the study of local alternatives, e.g., here and here.

This is old news, of course, but an interesting (and unpublished) variation on it might be of interest to you. When models are only locally wrong from what we assume, it’s possible we can’t ever reliably detect the model mis-specification based on the data, but yet that the mis-specification really does matter for inference. Thomas Lumley writes about this here and here.

2 Any argument you find yourself in is an unresolvable one

Anthropic principle of memetics: Invasive arguments.

3 Any philosophical debate you are in is a semantic quagmire

Related to the previous.

C’mon, why are we still arguing about free will? Is it because these words identify something profound and deeply ambiguous or just a deep hole that people can fall into and meet other people at the bottom of? How about free speech?

4 You have the perspective of someone who is like you

Because much of our experience of the world is based on how others respond to us, and that is based on features of our appearance that are hard to change, we all live in our own private filter bubble based on the world view. e.g. because I am a confident, white, English-speaking male of a particular generational cohort, I elicit particular responses from the people around me, that people who are not confident, not male, or not white, are less likely to elicit, even in a situation which is otherwise identical. I do not generally experience that alternative experience without role-playing, cross-dressing, or blackface, all of which are either taboo or difficult. Vice versa, people who look different from me are less likely to have a good insight into my perspective of the world. The term white privilege, as it is commonly used, presumably describes a particular manifestation of this general phenomenon.

The intriguing phenomenon for me is that, experientially, it seems hard for us to learn to compensate for the difference in world perspective, and we do tend to either erroneously assume our own experience is universal, or at least to do a bad job of understanding the differences between our experiences.

5 Often we want to know what the sampling bias is itself

In the previous section, I wondered about whether my perspective is constrained by where I come from and how people see me. Good-o. But which of these characteristics are important for the kind of perspectives on the world that I will attain? How important is it for my information environment that I am white? that I have a prestige accent? That I am a white-collar worker? etc. Knowing not just what I think, but how different the worlds are that we come from is a whole thing in itself. To consider: also in information sampling, interaction effects are what we are interested in.

6 Typicality

Subtle but important question: What is the relationship between average and typical, or even more subtle, modal and typical? Read Sander on typicality.

7 You have the perspective of your peers

Another influence on my perspective, distinct from who I am, is who I talk to. This may be people like me, if e.g. I am a mobile white-collar worker who gets to choose my community. Or it may be people unlike me, e.g. if I work in the service industry. TBD. See epistemic communities and/or inference on social graphs.

8 Hype cycles and Ponzi schemes

Where in the hype cycle do you encounter a product? Which is the most likely level that you will be at if you join a Ponzi scheme?

From the original Hobart essay, Sin, Secret, Series A.:

A social media site might turn out to be the reductio ad absurdum of the brand-as-lie/lie-as-Schelling-Point phenomenon, since the entire point of user interaction on the site is to make the lie true. If a site markets itself as the place where a certain kind of cool person hangs out, and says it boldly enough to the right audience, it becomes exactly that.

A corollary to this is that for you, every social media site peaks in utility right after you join. When I was barely cool enough to qualify for Quora, Quora was pretty cool to me — but to anyone who’d been on the site for six months, Quora was a formerly cool site now populated by lamers.

9 The Sleeping Beauty problem

An actual hardcore philosophical problem, which snuck in here as I am using it to teach probabilistic reasoning right now.