Constructivist rationalism

December 19, 2024 — December 19, 2024

Suspiciously similar content

On whether we make things, or allow them to evolve. I thought I first read about this in a passage from Hayek, but I can no longer find it. The idea was that we model ourselves as having more agency than we do. So, imagine the most fundamental unit of human scientific endeavour, the laboratory experiment: Say a scientist wishes to measure the boiling point of water. They might describe the steps in the experiment: pouring water into a test tube, heating it with a bunsen burner, watching a thermometer. Every step in that we might imagine as something simple, in which a human has total agency. And if we stop to think about it, pouring water is not so simple. Pouring is a complicated operation, involving the coordination of many muscles, the control of the flow of water, the balance of the container, the aim of the stream, the timing of the release. Do we solve the governing equations of water?

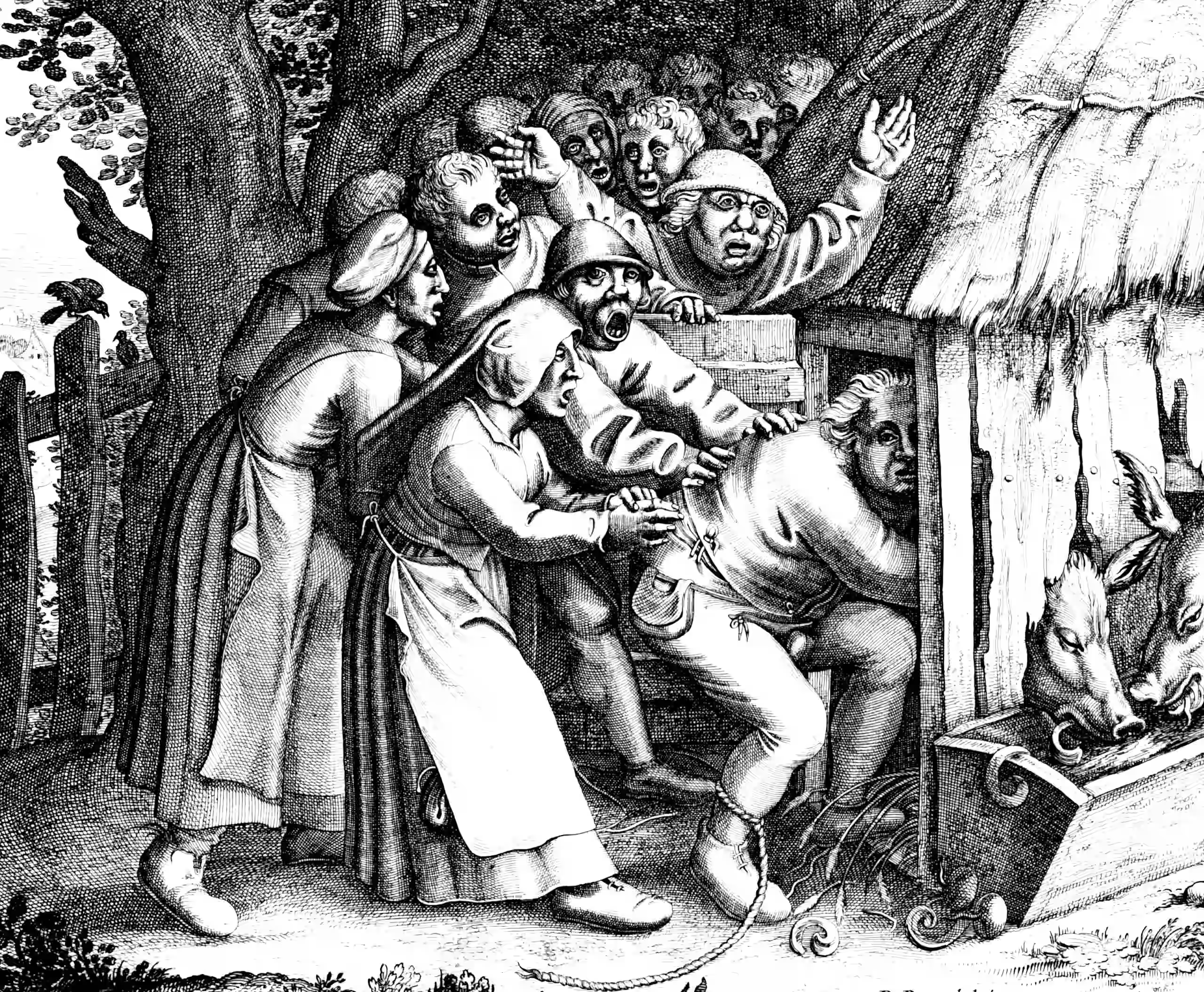

Friedrich Hayek identified a cognitive tendency he called constructivist rationalism. Constructivists, he argued, believe human reason is limitless and that complex structures result from deliberate design. To this mindset, society seems like a well-planned machine, often dismissing the value of tradition and spontaneous order.

As an antidote, Hayek championed critical rationalism, which recognises our cognitive limits and the unpredictable nature of evolution. Instead of seeing institutions as products of intentional planning, this view foregrounds how many beneficial structures emerge organically from individual actions and unintended consequences. In this view, seemingly irrational customs and evolved practices are all potentially load-bearing structures in society.

For Hayek, this was a critique of radical, utopian redesigns of society (for me, less so, but that is a story for another time); it seems to have gotten a lot of mileage in modern developmental economics.

This distinction raises a compelling question: do we really design the systems and technologies we rely on, or do we simply allow them to emerge and evolve without fully understanding how they work? It’s easy to think of ourselves as the architects of our environment, meticulously crafting every detail, but Hayek suggests the reality might be much messier and less controlled, that we might think of ourselves less as genetic engineers and more as gardeners when it comes to cultivating our environment.

I argue this holds for many more things than overtly social system, but is true in general of technology. What happens when the systems we depend on are more about emergence than intention? Many of the tools and platforms we use daily weren’t the result of a single, grand design. Instead, they’ve evolved through countless iterations, user feedback, and unexpected uses. Think about the internet—originally intended for academic and military communication, it has transformed into a global marketplace, social network, and information hub in ways its creators couldn’t have fully anticipated. Embracing this evolutionary view can help us better navigate the uncertainties of technological advancement and foster more resilient innovations.

Furthermore, recognizing the emergent nature of systems challenges us to adopt a more humble and flexible mindset. Instead of striving for complete control, we might focus on creating environments that support positive emergence.

TBC