Public speech norms as compatibility problem

Postel vs postal, legibility vs intelligibility

February 1, 2020 — May 25, 2022

Suspiciously similar content

In the free speech notebook I dumped lots of links and half formed ideas on the public sphere in general. In how to communicate I noted some communication advice which has been useful for me.

This placeholder is to remind me to revisit one idea in particular from that dump: Speech as a standards problem.

I mean this in the sense of technical standards (which USB connector plugs into what, which network protocols), rather than the moral sense (“we must maintain our high moral standards…”) although I argue that one difficulty is more or less that we are currently trying to find technical standards that encode moral standards. In any case, even in other domains, technical standards can end up being moral in the end, or at least, are not morally neutral, because they lead to winners and losers. cf Net Neutrality.

While the classical but somewhat fuzzy notion of social norms is possibly a more exact taxonomical classification of communication conventions, the alien and austere metaphor of technical standards brings clarity by allowing us to abstract away some of the confounding moral weight. Good, so here we go. Languages, dialects, accents, conventions of politeness and turns-of-phrase, social mores, considered as technical standards for interpersonal communication.

When it comes to communications, what is the cost of maintaining a standard? What does compatibility mean? Can we think about subcultural communication standards by analogy with their technical counterparts (Mac vs PC, iPhone vs Android, Lightning vs USB-C vs Bluetooth)? Are there equivalents to the various technical challenges involved in implementing a tech standard that we can translate to more nebulous social norms?

1 What kind of standard is human communication?

Let us start by imagining communication between humans as being structured like the OSI model, where the language itself (e.g. the English language) forms the lowest layer, and then on top of that we construct more abstract structures. So I might speak English, but I use it differently in different contexts; depending on who I am speaking with and how I wish to communicate with them, I speak a different dialect, and a specific register, i.e. style of speech. I do not use the same register amongst ESL speakers, friends, taxi drivers, and job interviews, for example. In the technical metaphor, these are something like different applications on the language-based network stack.

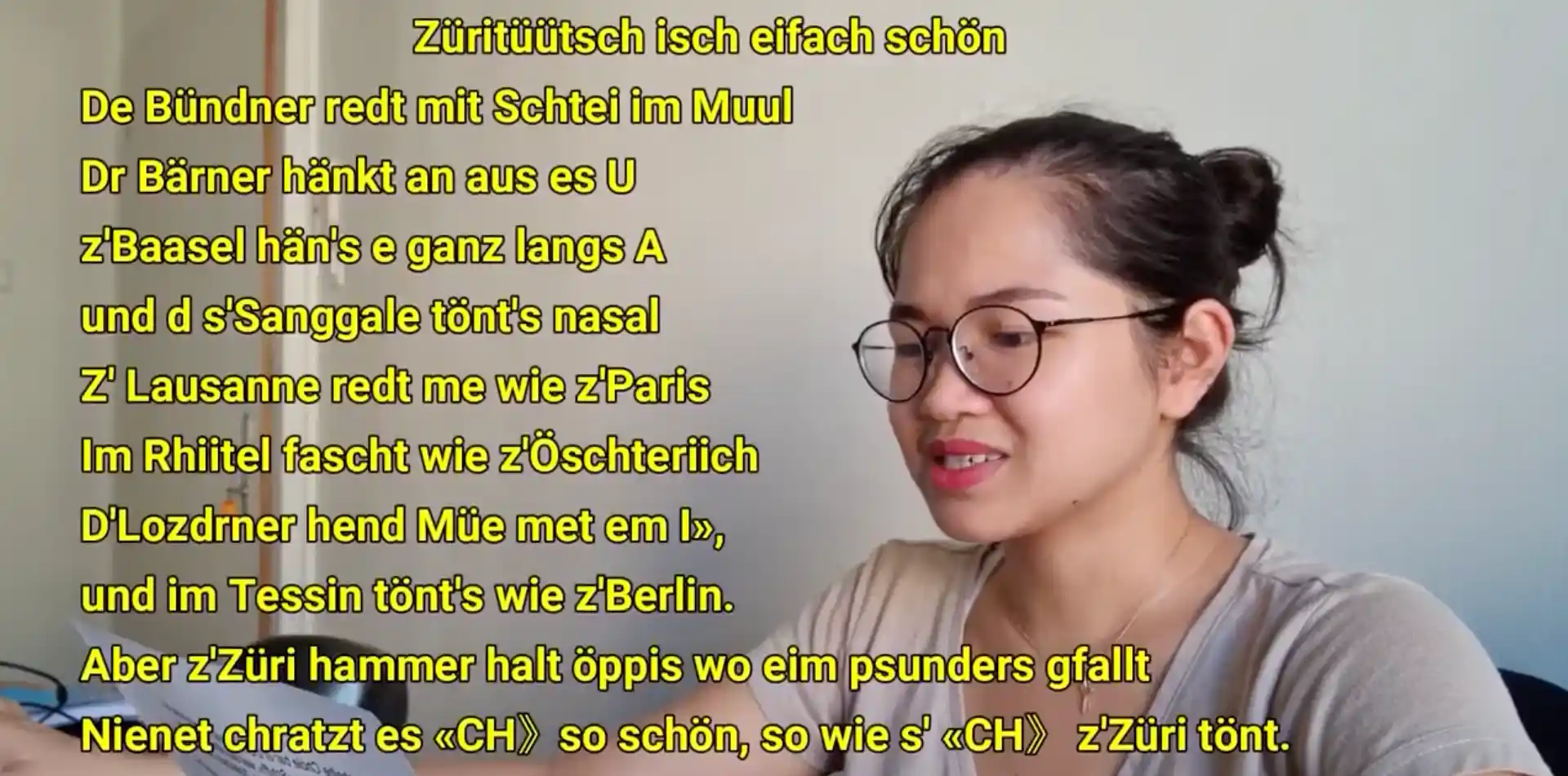

I speak 3 languages. Two of those are functional, if not eloquent, and one, my native language, is flamboyant, if not elegant.

Inside these languages, I can code-switch between a few different registers.

For example, in english, I can switch easily between registers that I might call Aussie bloke casual, early 2000s environmental activist, 2020s woke, office formal, Crocker’s rules, workplace assertive, blogging rhetorical, and others. There are many small details that go into each, and many subtleties in each. When speaking Aussie bloke, for example, a neophyte might use mate a lot, but as an experienced user I know that mate can very easily be ironical or distancing. Bud is easier for younger folks, or cunt to signal unambiguous intimacy. I do not have the same depth of understanding of each of these.

2 How much does it cost to maintain a standard?

Technical standards have costs, in implementation and compliance. How long does it take to learn a language? How long does it take me to a particular register?

As for learning those non-native languages, I can tell you that I invested hundreds of hours of class time, thousands of hours of self-study time. I also have an unknowable amount of immersion time; How much time did that chat over the kitchen counter with my flatmates add to my total language acquisition time? How much of the learning was multitasking, while I learnt something else?

Time spent learning the various language registers is harder to account. Once again, lots of the time was learning by immersion. I might have been fluent in English for since childhood, but I acquired many of those registers and dialects as an adult. If it is easy for me to speak like a 2000s environmental activist, that is due to a lot of long meetings in a previous career. There was a little bit of explicit training in there, but mostly learning-by immersion. Even if it did not feel like I was learning a linguistic register at the time, the fact remains that someone who has not logged a certain number meetings will not know the various terminology and the social mores of those particular ways of communicating. They may be many hours of immersion away from learning the local dialect.

I have a somewhat more precise estimate of how long it took me to learn workplace assertive communication, because it was something I dedicated time to, reading Back, Back, and Bates (1991) diligently and working through the exercises at the end of the chapters. I am going to say maybe 4 or 5 hours of dedicated study, then intermittent practice throughout the rest of my professional career. I suspect I am reasonably good at it, having negotiated a lot of potentially fraught discussions with satisfactory results and manageable stress load.

There are registers that I have failed to learn sufficiently well to communicate. For example, I have a poor track record with the register spoken by depressed people, and there is at least one depressed former friend who is convinced my manner towards them was intended to torture them for sport. This is despite my attempts to learn some basic psychological first aid. Possibly I could have done better in this case; or possibly I would have needed postgraduate clinical psychology training to negotiate her communicative needs at that point.

Some standards are hard to learn by design. If you have time to learn you can indicate that you are a member of the exclusive club of people who have time to learn this kind of abstruse confusing system (English spelling).

Some other stuff is anti-inductive.

Anyway, I am rambling.

Key point: costs time to learn each new dialect. Each additional culture is expensive. Each new set of linguistic oddities is

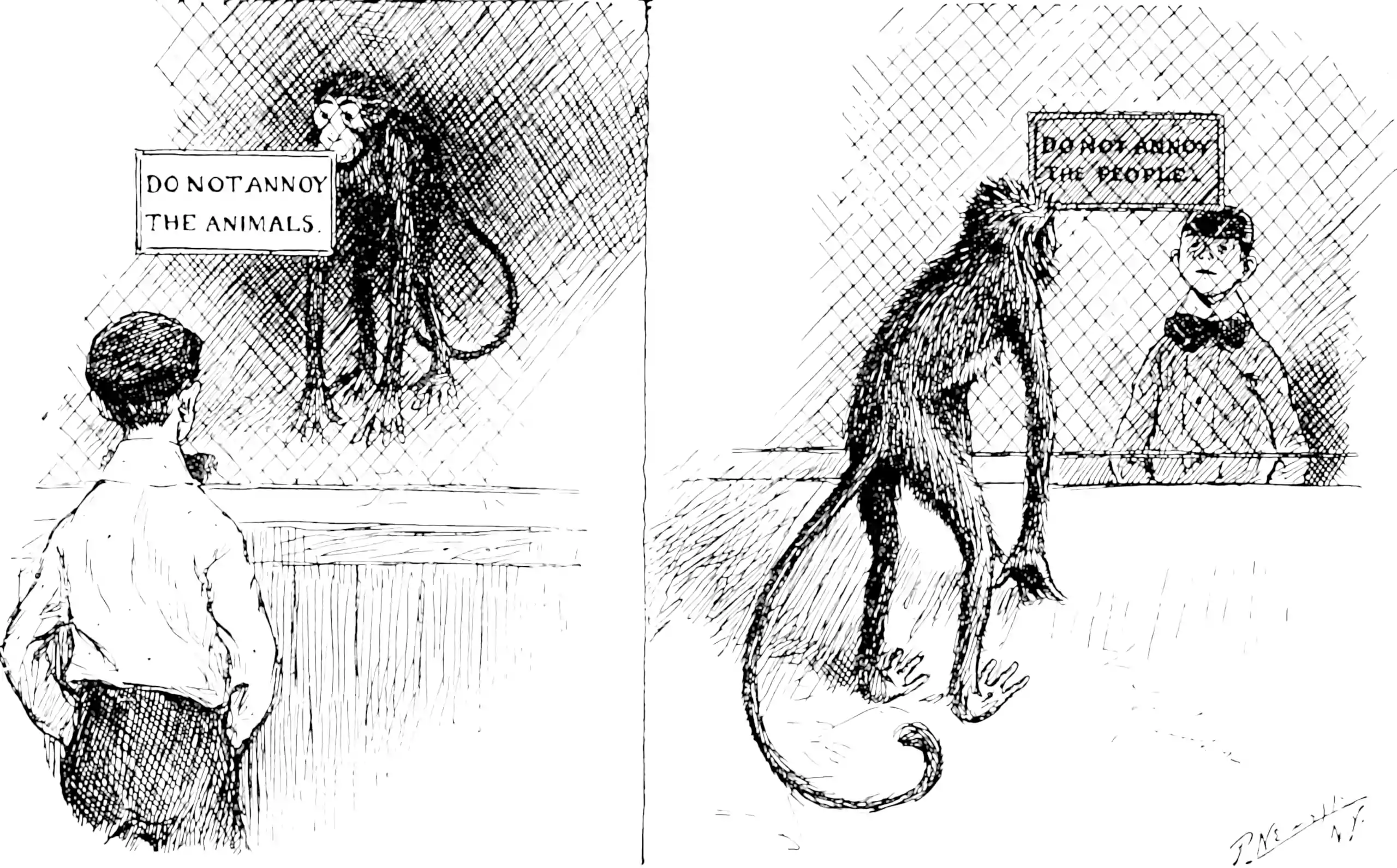

Cost of getting it wrong: people think you are stupid or malicious.

3 Speech standards seem more like moral standards

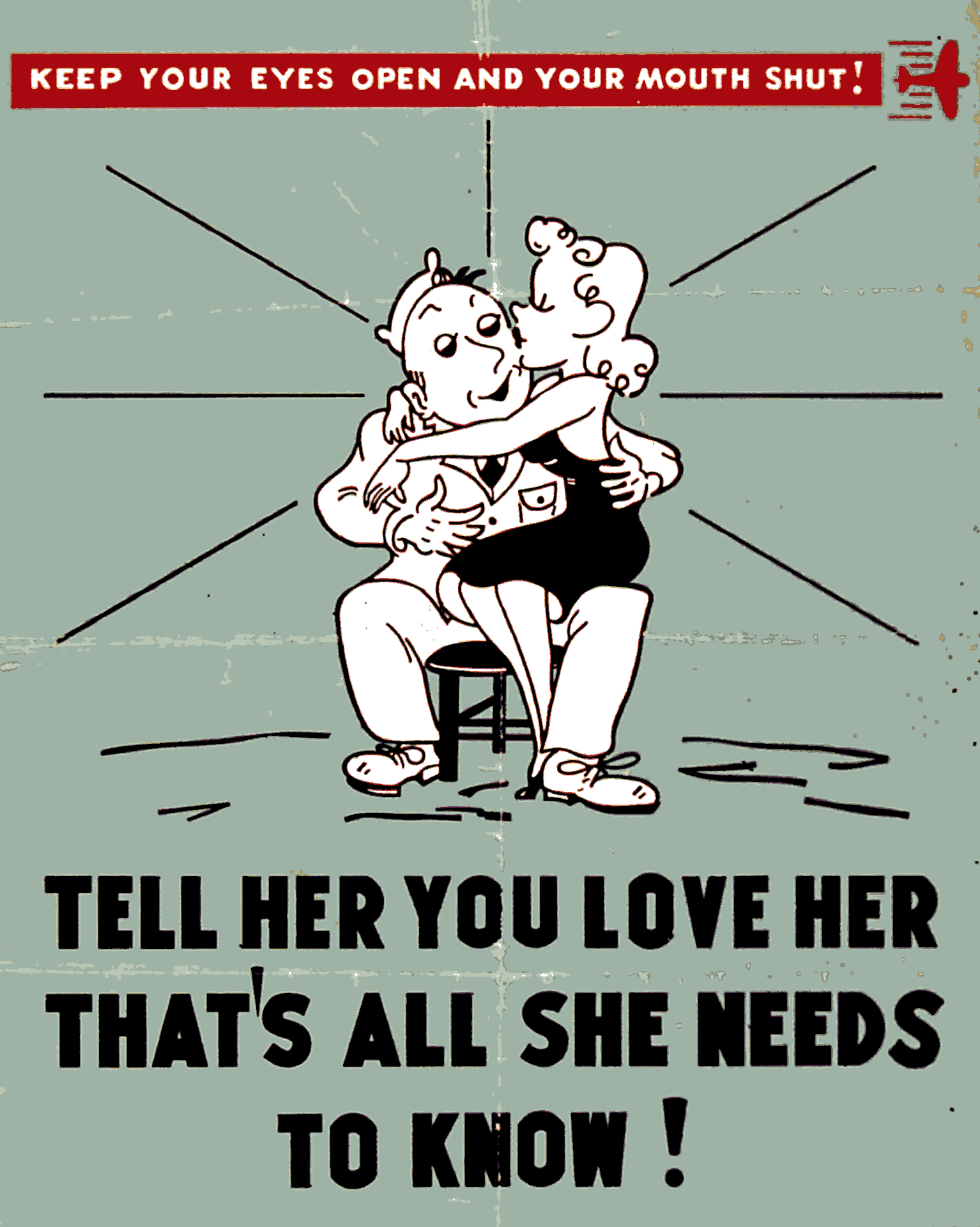

Unlike USB cables or bluetooth devices, we are unforgiving of people who adhere to a standard imperfectly.

In-group signalling iPhone vs Android.

4 What do we gain from a standard?

5 What is the simplest standard?

So, having considered that various standards are probably inevitable, and that we will always probably want to have lots of them, can we at least manage the complexity burden of standards?

Postel problems.

Consider Postel’s Law, or Spolsky’s notorious Martian headsets essay on that law:

[…] this is where Jon Postel caused a problem, back in 1981, when he coined the robustness principle: “Be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others.” […] Postel’s “robustness” principle didn’t really work. The problem wasn’t noticed for many years. In 2001 Marshall Rose finally wrote:

Counter-intuitively, Postel’s robustness principle […] often leads to deployment problems. Why? When a new implementation is initially fielded, it is likely that it will encounter only a subset of existing implementations. If those implementations follow the robustness principle, then errors in the new implementation will likely go undetected. The new implementation then sees some, but not widespread deployment. This process repeats for several new implementations. Eventually, the not-quite-correct implementations run into other implementations that are less liberal than the initial set of implementations. The reader should be able to figure out what happens next.

Apenwarr talks about this in terms of interoperating networks:

Postel’s Law is the principle the Internet is based on. Not because Jon Postel was such a great salesperson and talked everyone into it, but because that is the only winning evolutionary strategy when internets are competing. Nature doesn’t care what you think about Postel’s Law, because the only Internet that happens will be the one that follows Postel’s Law.

It would be pleasing for me if I could somehow tie in Stephen Wittens’ vocabulary for what standards are and how to imagine compatibility, especially since he also has a great interest in legibility and freedoms.

What, indeed is the simplest standard?

6 We can have fabulously intricate standards and that will feel great for everyone who has a voice in them

The social brain hypothesis argues that our brains are essentially for social interactions, and that the pinnacle of our mental agility might best be understood as an arms race of social intricacy. So we absolutely can maintain complicated social standards, and for all those who can find a place in them it will feel wonderful to be living their best social brain selves. The risk is that those who have a hard time participating in our intricate structure, e.g. outsiders and autistics, look defective, from the regard of an intricate standard. If they do not like the system it is because they are wrong not because the system is less inclusive of them than it could be.

Indeed. When we think of complicated procedures, we tend to think of bureaucratic make-work. But some complicated beautiful. Consider Chado (Watch 春茶会🍵🇯🇵 Real Japanese Tea Ceremony🌸Unintentional ASMR 😌). If we would like a marvellously complicated and intricate set of social rituals to be the flowering of western civilisation, then that is a choice that we can make. I can imagine this will be a delightful way for people to spend time, for at least some people.

I do have caveats about this plan, if it is a plan.

I think of famously ornate rituals such as tea ceremonies as being a good benchmark to evaluate complicated social rituals, because they do not hide their difficulty, nor their subtlety. There are masters, there are rankings, there are academies. There is also, crucially, still the option to get tea outside of the tea ceremony context. Green tea vending machines are a thing.

7 Speech standards that are excessively complicated will be paid for at the expense of the mission

Suppose that we have a workplace that is doing something important (delivering homelessness services to battered women, acculturating refugees, teaching schoolkids) etc. To the extend that a good speech standard helps the organisation to work together to deliver services to the intended recipients, it is valuing and helping those recipients. If it the speech standard, say because of advocacy by the staff, becomes so ornate that it begins to impair organisational efficiency, then it is valuing the desires of the staff over the desires of its actual constituency.

8 Networks and subcultures

Peyton Young analyzes what standards can propagate on a graph. (Burke and Young 2010; H. Peyton Young 1996) via network economics.

9 Standards are not “neutral”

We know this already in highly abstract technical domains. Cryptography nerds like to cite the NSA interference in cryptography standards.

- Silent Circle ditches NIST cryptographic standards to thwart NSA spying

- NSA Efforts to Evade Encryption Technology Damaged U.S. Cryptography Standard

- How far did the NSA go to weaken cryptography standards?

- NIST Refutes Allegations NSA Compromised Crypto Standards

Or the standards for how word processors exchange things: Standardization of Office Open XML.

We see this in language standards also. Back in my linguistics classes I learned that essentially all dialects are consistent and complete ways of communicating, and the only criterion for success in speech is that the content of your speech be understood.

But of course, we were full of the Chomskyian turn, and thinking about mathematization of abstract communication. In practice, real speech is about communicating not just facts but status. It would be nice if people were relaxed about spelling and pronunciation, but you need only to visit the comments section on… any part of the internet… to find people being shamed for spelling, or visit any pub to find someone who speaks the local dialect mocking low status accents, especially foreign ones.

10 Case study: English grammar police

- Mark Liberman Annals of Word Rage

- Language Log » Peeving

- Language Log » Prescriptivist poppycock

- Clare Foges argues that while the different dialects of English might be perfectly legitimate in themselves, some dialects will realistically always be more prestigious and so people should be taught to speak plummier, wealthier dialects to assist their ability to climb the status hierarchy.

- Spelling it out: is it time English speakers loosened up?

- Received Pronunciation

Quoted in Milroy and Milroy (1999):

For many years I have been disgusted with the bad grammar used by school-leavers and teachers too sometimes, but recently on the lunch— time news, when a secretary, who had just started work with a firm, was interviewed her first words were: “I looked up and seen two men” etc. It’s unbelievable to think, with so many young people out of work, that she could get such a job, but perhaps ‘I seen’ and ‘I done’ etc., is the usual grammar nowadays for office staff and business training colleges. (“Have Went”; Saintfield, N. Ireland)

For Milroy and Milroy (1999) or Fisher (1979) or Richardson (1980) the question of choosing a standard is the usual reason for choosing a standard — so that commerce may be conducted between people with a nearly-shared language.

To read: Baugh and Cable (1993);Cox (n.d.);Crystal (2005);Fisher (1979);Leith (2005);Milroy and Milroy (1999);Richardson (1980);Smith (1996)

11 Case study: White Australia dictation test

Robertson, Hohmann, and Stewart (2005):

The dictation test, a key element of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Cth),2 has always been associated with the question of race. It was administered to ‘coloureds’ and ‘Asians’ in order to have an apparently neutral reason to deport them. The last person to pass the test did so in 1909. It became ‘foolproof’, as it was designed to be: the applicant would be given the test in a language that their background firmly indicated they would not know and, upon failing, they would be told that the authorities could go on giving them tests in languages that they did not know, infinitely

12 Documented, simple, teachable standards are better

- Connect to legibility.

The more teachable a standard is the more inclusive it is. To be teachable it must be well documented, be as simple as possible, and minimise ambiguity. If standards are not teachable, or perhaps, can be learned only by deep immersion in the shared understanding of a particular culture, then they are … not really standards. In the technical world, we refer to inscrutable standards supported only by tacit knowledge as vendor lock-in. In the world of speech, they are often referred to as shibboleths.

13 Whack-a-mole, euphemism treadmill, and maintaining standards

I’m not deeply aware of the seething petri dish of memetic warfare that the USA seems to spend its time on, but it looks like a lot of what I thought of as innocent household items are highly charged symbols there, e.g. watermelon, milk, hawaiian shirts. A culturally sensitive approach to their 🚧TODO🚧 clarify

14 Which standard are we using?

Revisiting context collapse

Understanding Context Collapse Can Mean a More Fulfilling Online Life

A Deep Dive into the Harris-Klein Controversy, introducing Activist Style and Rational Style in arguments and showing how people using the languages of each are going to argue at cross purposes.

He doesn’t expect his identity to be an input to his arguments’ evaluation function, and from what aspects of his psyche they’re coming isn’t relevant. Not according to traditional Rational Style debate rules anyway, where evaluation functions only take the content of the argument. Identity politics means refusing to stay in this sandbox and the result is Activist Style, based on traditionally disallowed moves. [in Klein’s Activist Style] coupled ideas can’t just be discharged by uttering a magic phrase. The notion is ludicrous. Thinking in moral and political terms is not a bias, it’s how his job works and how his thought works. Implications and associations are an integral part of what it means to put forth an idea, and when you do so you automatically take on responsibility for its genealogy, its history and its implications. Ideas come with history, and some of them with debt. The debt has to be addressed and can’t be dismissed as not part of the topic — that’s an illegal move in Klein’s version of the rules.

15 A moderate amount of taking up space is an efficient standard

It is cheaper to evaluate hypotheses than to generate them, in science generally.

TBD: it is easier to evaluate scientists who generate hypotheses, than those who remain silent about the hypotheses they silently hold inside. Failing often is a great idea, as is looking stupid.

Clearly, there are people who feel better about looking stupid, and people for whom that is exposing a vulnerability.

Negotiating this?

16 Presentation, code switching, authentic self and such like

- Goffman (1978)

- The Costs of Code-Switching

- Advantages of code-switching Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, and Dussias (2020)

- Code-Switching and Assimilation in STEM Culture

17 Normative

Some standards that I find helpful to bear in mind. YMMV.

17.1 Assuming positive intent

An interesting application of iterated game theory in conversation.

Assuming Positive Intent is great in typical conversation.

Note that it is vulnerable to adversarial attack.

17.2 Explicit is better than implicit

17.2.1 Assertiveness

I really like their framing. They discuss assertive speech as a standard of communication that you can mutually agree upon, which if we all accede to it, will lower overall stress. It is kind of an emotional lingua franca.

I have a somewhat more precise estimate of how long it took me to learn workplace assertive communication, because it was something I dedicated time to, reading Back, Back, and Bates (1991) diligently and working through the exercises.

17.2.2 Asking over guessing

TBD

18 Incoming

Customary Practices of Musyawarah Mufakat: An Indonesian Style of Consensus Building (Anggita and Hatori 2020)

DRMacIver’s note on The costs of being understood is my favourite.

Autism and allism, esp Crompton et al. (2020)

America Against America: the Chinese de Tocqueville (Can this guy just tone down his passgro by two notches so that people can sit through it?)

Golden Paths are a light solution coordination in engineering. Choose a single standard to work with by default, and you can negotiate alternatives on an as needed basis.

Connect to how to communicate

What a globally suboptimal standard implies about local responsibility.

rhetorical standards

Elizabeth on Epistemic Legibility.

Stratechery by Ben Thompson, Portability and Interoperability

Michael Hobbes, Panic! On the Editorial Page

John McWhorter, The Neoracists summarises the confusion my Dad experiences negotiating the complicated and landmine-filled terrain of contemporary racism advice:

- When black people say you have insulted them, apologize with profound sincerity and guilt. But don’t put black people in a position where you expect them to forgive you. They have dealt with too much to be expected to.

- Black people are a conglomeration of disparate individuals. “Black culture” is code for “pathological, primitive ghetto people”. But don’t expect black people to assimilate to “white” social norms because black people have a culture of their own.

- Silence about racism is violence. But elevate the voices of the oppressed over your own.

- You must strive eternally to understand the experiences of black people. But you can never understand what it is to be black, and if you think you do you’re a racist.

etc.