Social norms

October 7, 2019 — April 13, 2022

Asch conformity experiments, Schelling points, illusory norms via pluralistic ignorance or majority illusions.

1 Automated

Anders Sandberg, on AI versus social norm enforcement:

We are subject to norm enforcement from friends and strangers all the time. What is new is the application of media and automation. They scale up the stakes and add the possibility of automated enforcement […] . Automated enforcement makes the panopticon effect far stronger: instead of suspecting a possibility of being observed it is a near certainty. So the net effect is stronger, more pervasive norm enforcement…

…of norms that can be observed and accurately assessed. Jaywalking is transparent in a way being rude or selfish often isn’t. We may end up in a situation where we carefully obey some norms, not because they are the most important but because they can be monitored.

I think Anders is approaching Goodhart’s law.

2 Marit ayin

Marit Ayin, a principle in Jewish law and moral philosophy, has come up in conversation recently several times in the context of setting workplace norms. It seems to serve as a complement to gaslighting. In combination with dan l’kaf zechus (“judge your fellow favourably”) which sounds rather like a Postel’s Law for ethics.

Here is one of many online explanations I could find:

When I do something that looks wrong, even if I have a perfectly good and innocent explanation, the damage is done. …If I enter a non-kosher restaurant to use the facilities, while I have not broken any law of keeping kosher, I have bridged the divide between kosher and not kosher, and invite others to do the same. But there’s a deeper reason not to do something that just looks wrong, even if it isn’t wrong, and even if no one is looking. And that is because not only can such activity affect others, it can affect us too. Actors know that when you play a character, you can sometimes become that character. The self we project to others can sometimes be absorbed into our own identity. And so by looking like you are doing something wrong, you may come to actually do it.

This is a useful concept (if not a precept) I do need to discuss this concept from time to time. In particular, I think this gets at an element of conspicuous morality that is it is best not to dismiss as “mere” virtue signalling.

3 Norm maintenance and attainment at the individual level

Sacred Values Are How Ethical Injunctions Feel From The Inside.

David MacIver: Jiminy Cricket Must Die

It is useful here to have the distinction between a belief and an alief. A belief is something that you think to be true, while an alief is something that you feel to be true (they’re called a-liefs because they become b-liefs). Haidt’s research suggests that aliefs and not beliefs are the foundation of people’s moral “reasoning”.[…]

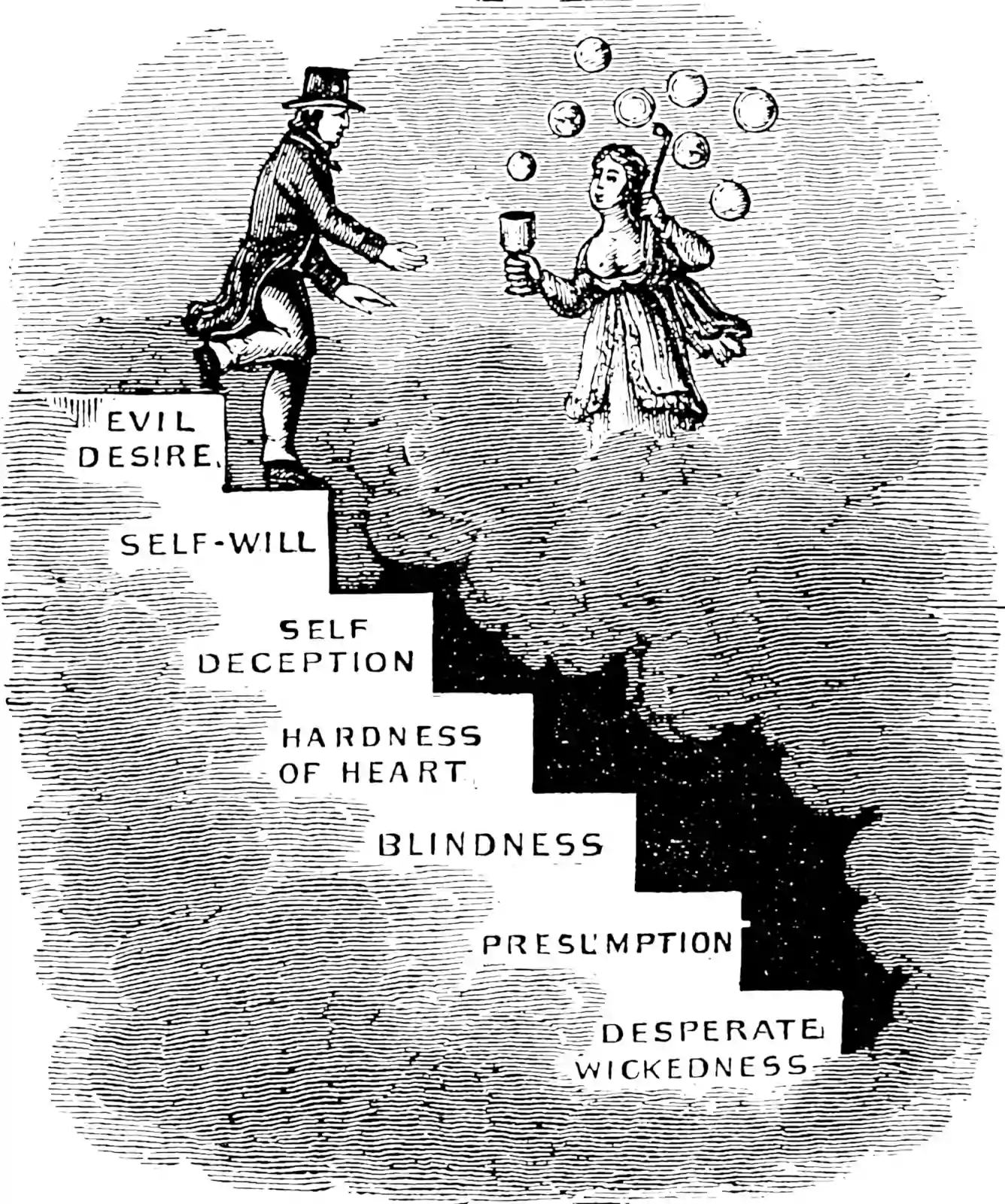

How do we acquire these norms (Green calls the process normation)? Bluntly, operant conditioning.

When we obey the norm, we are often rewarded. When we disobey it, we are often punished. Sometimes this is enforced by other people, sometimes this is enforced by reality, sometimes this is enforced by our own latent fears about standing out from the crowd (itself a feeling of conscience that we have acquired—standing out makes you a target).

The conditioning trains our habits, and our feelings, to comply with the norm because we learn at an intuitive level to behave in a way that results in good outcomes—behaviours that work well are repeated, behaviours that work badly are not, and we learn the intuitive sense of rightness that comes with “good” behaviour from it.

So what does conscience feel like? Conscience feels like following the path in the world that has been carved for you via your training. When you stick to the path, it feels right and good, and as you stray from it the world starts to feel unsettling, and even if you no longer fear being punished for it you have learned to punish yourself for it.

See also Movement design.

3.1 Chesterton’s norms

Why do we do it that way? 🏗️