Majority illusions and filter bubbles

Toxic cascades, squeaky wheels and social dark matter; the difficulties of estimating what all people think from the ones you see

September 22, 2019 — February 17, 2025

Suspiciously similar content

Inference is easy when they teach you about it in school, but in the real world, it’s hard. Imagine you’re trying to gauge how many cows in a herd have a particular quality — say, a genetic trait linked to higher milk yield. Since cows mostly mix evenly with one another, you can simply select a few at random and get a pretty accurate picture of the whole herd.

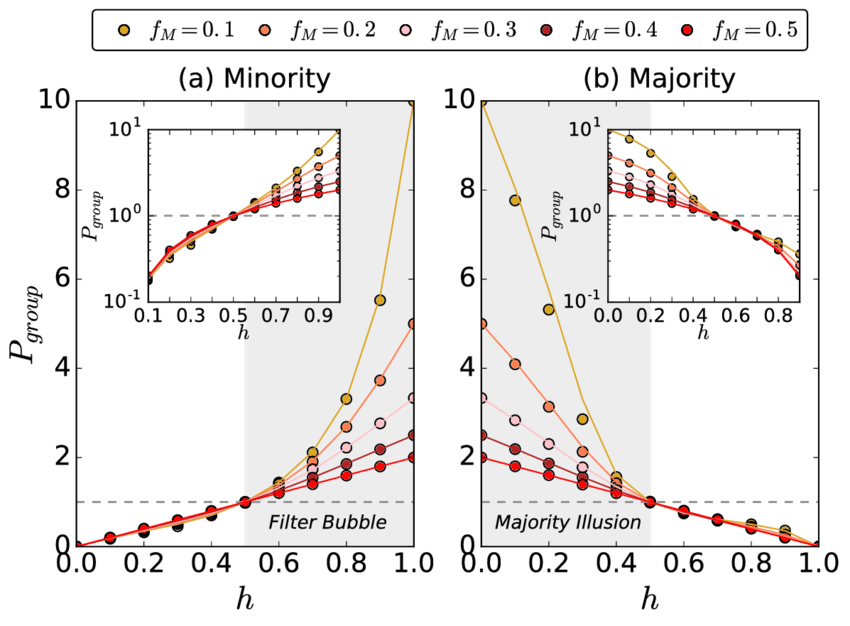

Now, consider a human scenario. Suppose you want to estimate the prevalence of a niche political opinion. You might ask a random person how many of their friends share that view. However, because of the Majority Illusion, even if only a small fraction of people hold that opinion, a few highly connected individuals (the social “hubs”) can make it seem much more common. These hubs appear in many people’s friend circles, so their rare opinion is overrepresented in local samples, even though it’s rare globally.

This is one of the challenges of inference on social graphs that really messes with us when we try to understand opinion dynamics. This insight is one of those that seems trivial in hindsight, but people are terrible at articulating in advance. Related, perhaps a consequence of this, is pluralistic ignorance.

Another major problem is that the people who participate in public discourse are weird, and moreover, the people whose opinions are disseminated on social media are even weirder. This is the social dark matter problem; you are going to see stuff that is way crazier than you would expect from the general population.

Here, I would like to think about things that resemble the majority illusion.

1 Incoming

Duncan Sabien, Social Dark Matter

-

There’s an analogy to be made with US politics: political analysts refer to “what the people want,” when in fact a fraction of “the people” are registered voters, and of those, only a percentage show up and vote. Candidates often try to cater to that subset of “likely voters”— regardless of what the majority of the people want. In porn, it’s similar. You have the people (the consumers), the registered voters (the customers), and the actual people who vote (the customers who result in a conversion — a specific payment for a website subscription, a movie, or a scene). Porn companies, when trying to figure out what people want, focus on the customers who convert. It’s their tastes that set the tone for professionally produced content and the industry as a whole.