Tribal sorting and polarization

Social fragmentation by browser cookies

February 12, 2017 — October 8, 2022

Content has been recycled from an increasingly inaccurately renamed “filter bubbles” notebook. See also media weaponization, memetics, and epistemic communities etc.

1 In news

Theirtube is a YouTube filter bubble simulator that provides a look into how videos are recommended on other people’s YouTube. Users can experience how the YouTube home page would look for six different personas. Each persona simulates the viewing environment of real YouTube users who experienced being inside a recommendation bubble through recreating a YouTube account with a similar viewing history. TheirTube shows how YouTube’s recommendations can drastically shape someone’s experience on the platform and, as a result, shape their worldview. It is part of the Mozilla Creative Media Awards 2020 — art and advocacy project for examining AI’s effect on media and truth, developed by Tomo Kihara.

I think the proverb “Fish discover water last” can also be said about how we are blind to the nature of the recommendation bubble that we are in. Nowadays with an AI curating almost all of what we see, the only way for a person to get a better perspective on their own media environment is to see what others’ look like. By offering a tool to understand what the other recommendation bubbles look like, we hope to help people to get a better perspective on their own recommendation bubbles.

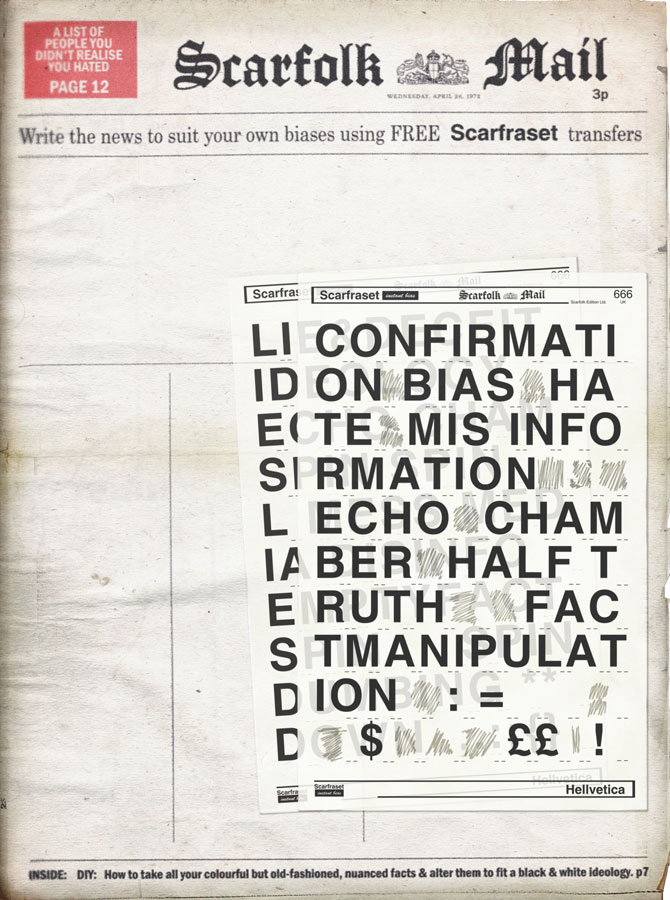

…newspapers such as the Scarfolk Mail realised that they no longer needed to provide actual content: Readers only saw what they wanted to see and comprehended what they wanted to comprehend.

“Data journalism” has created interesting tools. But do people care about data? Are facts persuasive? Even if facts are persuasive, are facts enough? As Gilad Lotan anecdotally illustrates, merely selecting facts can get you your own little reality, without even bothering to lie.

Let’s get real; for the moment, reasoned engagement with a shared rational enlightenment doesn’t dominate the media. Bread and circuses and kompromat and gut-instinct do.

Hugo Drochon argues that interest in conspiracy believers is itself a kind of collective hysteria and there are not so many conspiracy believers in The Conspiracy Theory Bubble. (He does argue for an increased salience of conspiracy believers.

Kate Starbird’s study of agents provocateur in online campaigns.

For a false binary, try Nick Cohen, Trump’s lies are not the problem. It’s the millions who swallow them who really matter:

Compulsive believers are not just rednecks. They include figures as elevated as the British prime minister and her cabinet. […]

Mainstream journalists are almost as credulous. After decades of imitating Jeremy Paxman and seising on the trivial gaffes and small lies of largely harmless politicians, they are unable to cope with the fantastic lies of the new authoritarian movements. When confronted with men who lie so instinctively they believe their lies as they tell them, they can only insist on a fair hearing for the sake of “balance”. Their acceptance signals to the audience the unbelievable is worthy of belief.

This is a shallow causal analysis; However, thinking about the credulity of people in power is interesting.

Alexis Madrigal, What Facebook Did to American Democracy. Buzzfeed, Inside the partisan fight for your newsfeed:

The most comprehensive study to date of the growing universe of partisan websites and Facebook pages about US politics reveals that in 2016 alone at least 187 new websites launched, and that the candidacy and election of Donald Trump has unleashed a golden age of aggressive, divisive political content that reaches a massive amount of people on Facebook.

Thanks to a trinity of the internet, Facebook, and online advertising, partisan news websites and their associated Facebook pages are almost certainly making more money for more people and reaching more Americans than at any time in history. In some cases, publishers are generating hundreds of thousands of dollars a month in revenue, with small operations easily earning five figures thanks to one website and at least one associated Facebook page.

At its root, the analysis of 667 websites and 452 associated Facebook pages reveals the extent to which American online political discourse is powered by a mix of money and outrage.

(Goel, Mason, and Watts 2010):

It is often asserted that friends and acquaintances have more similar beliefs and attitudes than do strangers; yet empirical studies disagree over exactly how much diversity of opinion exists within local social networks and, relatedly, how much awareness individuals have of their neighbours’ views. This article reports results from a network survey, conducted on the Facebook social networking platform, in which participants were asked about their own political attitudes, as well as their beliefs about their friends’ attitudes. Although considerable attitude similarity exists among friends, the results show that friends disagree more than they think they do. In particular, friends are typically unaware of their disagreements, even when they say they discuss the topic, suggesting that discussion is not the primary means by which friends infer each other’s views on particular issues. Rather, it appears that respondents infer opinions in part by relying on stereotypes of their friends and in part by projecting their own views. The resulting gap between real and perceived agreement may have implications for the dynamics of political polarization and theories of social influence in general.

A central idea in marketing and diffusion research is that influentials— a minority of individuals who influence an exceptional number of their peers— are important to the formation of public opinion. Here we examine this idea, which we call the “influentials hypothesis,” using a series of computer simulations of interpersonal influence processes. Under most conditions that we consider, we find that large cascades of influence are driven not by influentials but by a critical mass of easily influenced individuals. Although our results do not exclude the possibility that influentials can be important, they suggest that the influentials hypothesis requires more careful specification and testing than it has received.

On the right, audiences concentrate attention on purely right wing outlets. On the left and centre audiences spread their attention broadly and focus on mainstream organizations. This asymmetric pattern holds for the linking practices of media producers. Both supply and demand on the right are insular and self-focused. On the left and centre they are spread broadly and anchored by professional press.

These differences create a different dynamic for media, audiences, and politicians on the left and right.

We all like to hear news that confirms our beliefs and identity. On the left, outlets and politicians try to attract readers by telling such stories but are constrained because their readers are exposed to a range of outlets, many of which operate with strong fact-checking norms.

On the right, because audiences do not trust or pay attention to outlets outside their own ecosystem, there is no reality check to constrain competition. Outlets compete on political purity and stoking identity-confirming narratives. Outlets and politicians who resist the flow by focusing on facts are abandoned or vilified by audiences and competing outlets. This forces media and political elites to validate and legitimate the falsehoods, at least through silence, creating a propaganda feedback loop. …

The highly asymmetric pattern of media ecosystems we observe on the right and the left, despite the fact that Facebook and Twitter usage is roughly similar on both sides, requires that we look elsewhere for what is causing the difference.

Surveys make it clear that Fox News is by far the most influential outlet on the American right — more than five times as many Trump supporters reported using Fox News as their primary news outlet than those who named Facebook. And Trump support was highest among demographics whose social media use was lowest.

Our data repeatedly show Fox as the transmission vector of widespread conspiracy theories.

This is a strong claim; I have seen more or less the contrary asserted about which side of politics is more insular— I suspect this comes down to definitions of attention.

Farrell (n.d.) claim Fox News moved the 2008 presidential election Republican vote share by 6.3% to the right. I have not read this article yet.

In other results, we estimate that removing Fox News from cable television during the 2000 election cycle would have reduced the overall Republican presidential vote share by 0.46 percentage points. The predicted effect increases in 2004 and 2008 to 3.59 and 6.34 percentage points, respectively. This increase is driven by increasing viewership on Fox News as well as an increasingly conservative slant.

I have not yet seen how much real analysis is done in (Garimella et al. 2018) about which is is claimed:

The study identifies three essential roles for Twitter users. Partisan users both consume and produce content with only a one-sided leaning and enjoy high appreciation measured by both network centrality and content endorsement. Gatekeepers have a central role in the formation of echo chambers because they consume content with diverse leanings but choose to produce only content with a one-sided leaning. Bipartisan users produce content with both leanings and make an effort to bridge the echo chambers, but they are less valued in their networks than their partisan counterparts.

A methodology that clusters into three discrete groups smells funky but I really need to read the paper to see what they actually did.

So let’s say you’re a media owner who’s “all business,” caring only for the bottom line, looking to keep shareholders and owners happy, buy yourself some expensive houses, and/or get yourself or your friends re-elected. Without a doubt, the journalists who are prepared to tell readers the truth—even about you and your friends!—can only be a hindrance, and are best shut up or rid of, to the extent possible.

2 Game-theoretic models for

(Cohen 2012; Hales 2005; Hao and Leung 2011; Matlock and Sen 2007; McAvity et al. 2013; Oh 2001)

3 Incoming

NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, Polarization Report

Ian Leslie, The differences of minor narcissists

differences don’t cause conflicts; conflicts create differences. Members of a group seize on differences in order to affirm their own identity. A feedback loop ensues: differences are invented or enlarged, which stimulates further animosity, which magnifies differences, and so on.

Not Boring by Packy McCormick, Amplified Tribalism

Irrational Institutions #2 File under filter bubbles, reality bubbles, subculture dynamics.

Novoa et al. (2023)

The use of category-referring statements, also known as generics (e.g., “Democrats want to defund the police”), may contribute to polarization by encouraging the adoption of broad conclusions about political categories that ignore variation within each political party. […] These findings suggest that the use of generic language, common in everyday speech, enables inferential errors that exacerbate perceived polarization.

The Outsiders - by Leighton Woodhouse

In short, the autonomous pole is where cultural producers create cultural products expressly for other cultural producers. The heteronomous pole is where they produce for non-producers. Think Terence Malick versus Michael Bay.