Life-adjusted quality years

Whether to come to our party, if you like parties

March 11, 2022 — March 15, 2022

Suspiciously similar content

Assumed audience:

People I wish would celebrate life with me, who want a case study on how to manage their risk budget

Here is the scenario: There is a party coming up in Sydney. It’s a special one, a significant occasion for some important friends. Some of the people who will go I haven’t seen for ages. I would like to see them, but maybe the time is not right yet. Should I go to it? How do I decide this now, in 2022?

(OK, you got me. There is an actual party, and I am actually running that party, but let us imagine that I am a potential party-goer for a moment. More broadly, I’m hoping this case study will be useful for people in evaluating their own COVID activity risks right now, even if the event details are different or the local risks are different.)

The party has a certain amount of risk (and a certain amount of fun, I hope) attached to it because it will contain some fun risky activities I haven’t done in a while, like dancing and chatting. How do I think about deciding whether to go to such a party as this?

There are two risk management questions here I am concerned about:

- What is the risk of this event to me in absolute terms?

- If I am prepared to go to this kind of event at some point, is now the right time to go to it, or should I hold out for a future party?

#1 is pretty well understood now, if not precisely. And #2 is a bit more nebulous and a bit newer.

1 What is the risk of this event to me in absolute terms?

I guess the risk at the top of my mind is COVID. This is a fairly standard risk to worry about by now, and the tools to evaluate and manage it are well-understood. Step one: I need to evaluate the risks in local context. What the projected risks in Sydney are, what kind of party is it and so on. For my risk modelling, I endorse Elizabeth van Nostrand’s recommendation of the Bazant lab COVID-19 Indoor Safety Guideline for indoor events, although the classic microCOVID Project is a little easier to use and easier to explain, so it kind of depends on taste and context — See my covid notebook for some user notes. For now, I’ll lean on the microcovid one. I can drill down those risk evaluations in greater detail in my own time — that is why I have a notebook full of COVID resources.

Ballpark estimate, the risks of getting COVID at the party I am thinking of are maybe 6% if everyone has a fresh negative RAT (Killingley et al. 2022), going up to 13% if it is random people off the street. (In fact the party has two bits; I am rating the riskier part). I personally am triple vaccinated and I had COVID two months ago, so I suspect the odds there are somewhat lower for me, but let us be pessimistic.

So if I get COVID, how bad is it for me?

There are various other COVID risks we might want to consider here — travel or life disruptions due to isolation, the long-term effects of respiratory diseases, even the very anxiety I experience from worrying about COVID; these are all real factors for people in some circumstances. For various reasons, none of those loom very high in my own personal priorities. For that reason, and for the sake of the current case study, I’ll keep it simple and stick to the big one: death. We can run the figures again for other possible risks.

Annoyingly, we still really do not know the virulence (i.e. deadliness) for the dominant omicron variants of COVID with much precision at all.1 but let us say that it is 10% as lethal as the delta variant, which seems to be reasonable. If I am 75 years old my risk of dying from Omicron when I catch it is about 0.5% (plugging in the data from wikipedia which seems suspiciously pessimistic looking at the Australian stats but OK, let us run with that). If I am 25, it is about 0.01%, according to the same source. I have no further risk factors myself (immune-compromise, diabetes…), but if I did I could estimate their importance here. I have seen various rules of thumb around, e.g. “each extra risk factor adds 10 years to my age”, but I do not know enough to endorse these rules of thumb myself, so I will put that aside.

OK, but what do these numbers mean in practice? How do they compare to the other risks in my life?

One point of comparison could be past influenza outbreaks. The 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak… plausibly had ballpark the same virulence as the current COVID Omicron strain. That is not to diminish the importance of COVID; it is still a risk. But also, influenza sucks and we have gotten over that (possibly we have gotten too blasé about influenza). H1N1 did not stop me travelling in 2009, and in fact maybe that short intense respiratory sickness that I had while travelling in Indonesia was H1N1 🤷? Back then it felt totally #worthit.2

Alternatively, a neat way of comparing small risks is Micromorts. One micromort is a 1-in-a-million chance of death. We can compare risk of activities by number of micromorts of risk they involve. If I were 75, my 75-year-old self would accrue about 500 micromorts risk of death by going to the party. As a 25-year-old, I would accrue about 1 micromort of risk of death by going to the party. 55-year-olds are somewhere in between at about 50 micromorts, FWIW, which is to say, much closer to 25-year-olds than to 75-year-olds.

We could also estimate what I would need to do to undo the effects of COVID on my risk of death. How much being healthy is necessary to undo the risks of COVID? Back-of-the-envelope calculation reveals that skipping red meat for a week, or eating 10 serves of vegetables will get me back, on average, to where I was in terms of life expectancy after catching COVID. That’s as a 25-year-old. As a 75-year-old, I would need to be vegetarian for a year.

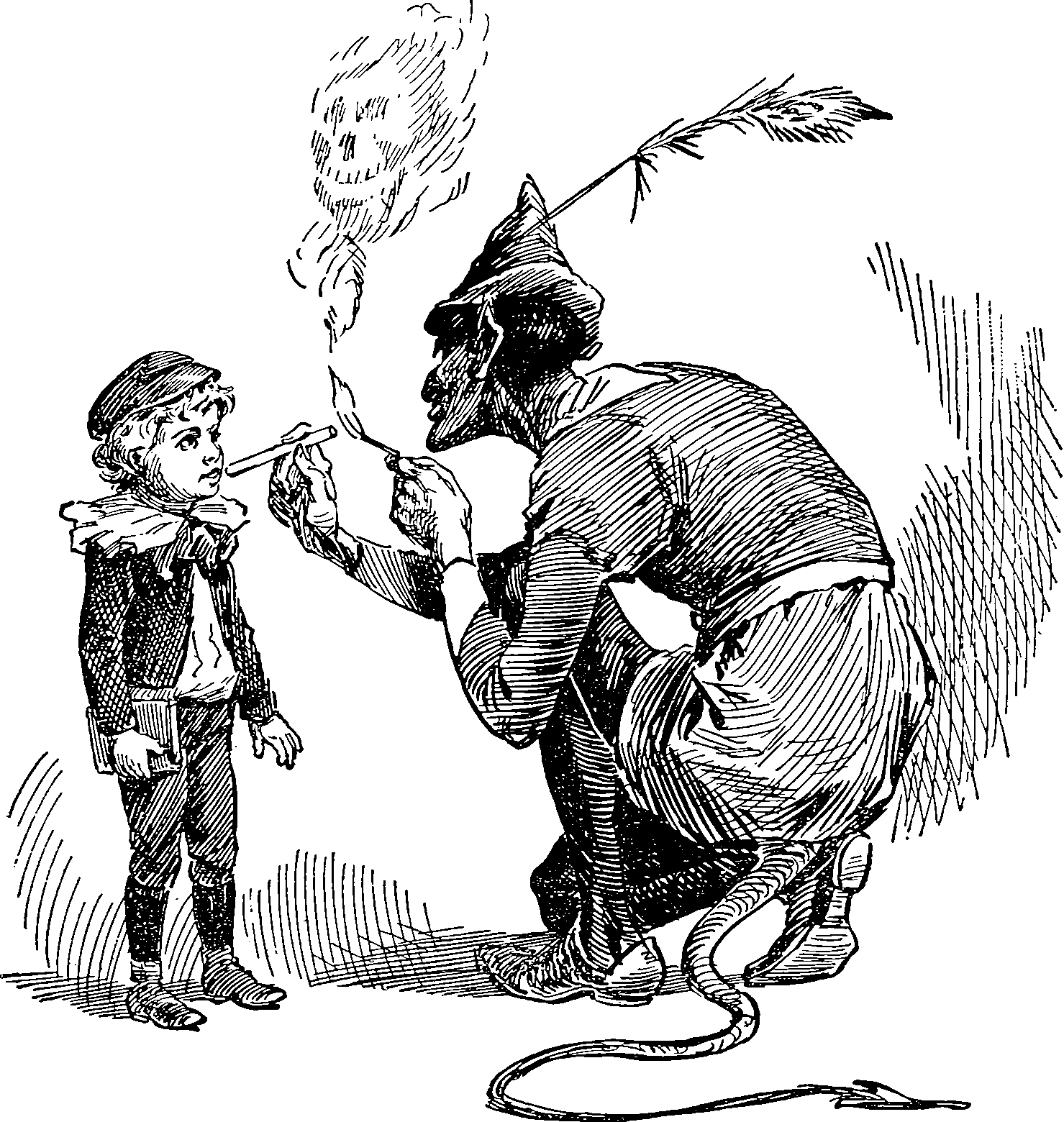

Let us assume that most everyone at the party has had a negative RAT test that morning and run with that risk estimate. By comparison, a risk equivalent for my 25 yo self is smoking half a cigarette or travelling 50km by motorbike. For my 75 yo self, it is equivalent to smoking 175 cigarettes, or riding 2500km by motorbike.

For the 25-year-old me, this is a no-brainer. For the 75-year-old… look, I myself would not take that risk unless it was important. I would not smoke 175 cigarettes every day. On the other hand, if not every day, which days should I consider taking such risks? That leads us to question #2.

2 If I am prepared to go to this kind of event at some point, is now the right time to go to it, or should I hold out for the next one?

This depends, but now is a pretty good time. Let us suppose that I am keen to go to my friends’ parties, at least a few of them, before I die, and so I am prepared to allocate some proportion of my overall life risk budget to seeing those friends. If I intend to go to a party again one day, is that day today? Is today a good investment of my risk budget, or will I get a better offer later?

IMO, if I am an average person, if this party is one of the ones that is worth spending some risk budget on, I should not wait. Maybe I do not wish to go to every party, but if there are parties of high value to me, I should go to them now. Waiting implies that I believe that the risk will get lower later, which does not seem reasonable. I have no guarantee that the world will offer me a better risk deal later. What I face right now is a qualitatively understood risk, at a low ebb. COVID is about and not great, but also not terrible. The population here is one of the most highly vaccinated in the world. Travel is possible, mostly. Floods are receding for now, and a new drought has not yet arrived. We live in a country which, despite all our terrible decisions, still has affordable health care and some kind of safety net to take the edge off the contagions. I do not know when I will find such a good deal again.

But later… What can we say about later? Consider COVID: Long term, no one knows what COVID will do. Gradually petering out to some non-threatening variant? New varieties? Being forgotten while we deal with the encroaching Dengue fever and Chikungunya and Japanese encephalitis outbreaks? Some new disease entirely? We do not have great long-term predictions for the future pandemics.

Oh and that is just disease! Meanwhile the world is full of warmongering by armed nuclear powers, climate change is outstripping the milquetoast IPCC predictions, floods are rendering people homeless, bushfires are shutting down communities, supply chains are breaking apart, trade wars are escalating, landslides and extinctions wrack the ecosystems, borders are closing, financial markets tumbling… The windows of safety and prosperity in which we can do parties are getting scarcer. The windows of certainty in which we can even attempt to plan parties are fractured. The times when we are not rescuing our neighbours from floods, or fighting bushfires, or stuck by travel restrictions, cancelling the parties we hoped for, those are the times when we need to enjoy ourselves before rolling up the sleeves for the next round.

I’m not arguing that we, individually or collectively, are doomed. My point is precisely that I don’t know that. What I am arguing is that increased risk is likely the new normal. Managing risk, choosing to raise when we can and fold when we cannot, is how we play the poker game of life. The person who will do well in the 21st century is the person who can recognise when the opportunities around them are good ones.

Comparative certainty is an intermittent luxury that we need to make the best use of when we have it. Seising the fun that you can have while times are better, so that you have stockpiles of fun for when things go south, that is the move that minimises overall lifetime risk. I think it is worth it for me to go to the party (if inshalallah, it actually happens) because things are as good as I can hope for right now. The alternative is missing out on the things that make life worthwhile, or alternatively, breaking my resolve and going to even riskier parties.

So for me, right now, it makes sense to go to the party, and see the people I am missing while I can do so.

Not everyone has my circumstances, of course. If I had a temporary illness, or someone near to me did, then later on that illness might not be a trouble for me any longer. In that case I have good information that the risk for me or my loved one is temporarily higher right now; and in that case I might get a better deal by waiting.

On the other hand, for the actual me, right now is a pretty good deal, as far as risk goes.

3 Appendix A: How about mediocre parties?

UPDATE: Apparently this needed saying.

Should I take every opportunity to go out into the world? If you want, but this implies that the only factor that matters to you is quantity, not quality. For most of us that is not the case; we want to see certain people and have certain experiences rather than going to every local bingo night we can get our hands on.

For most of us, the right metaphor is, as mentioned above, risk budget. Going to every bloody party will expose you to risk of disease, for sure, but it will also expose you to the risk that the mediocre party that did not bring you much joy is the one where you catch COVID, and then you are in isolation for the higher yield, more awesome parties.

The goal would be: If I cannot avoid COVID risk, I want to get a good deal for it.

4 Appendix B: What is it like in Sydney right now?

At time of writing it is fine where I am, thanks for asking, although a few friends have been flooded.

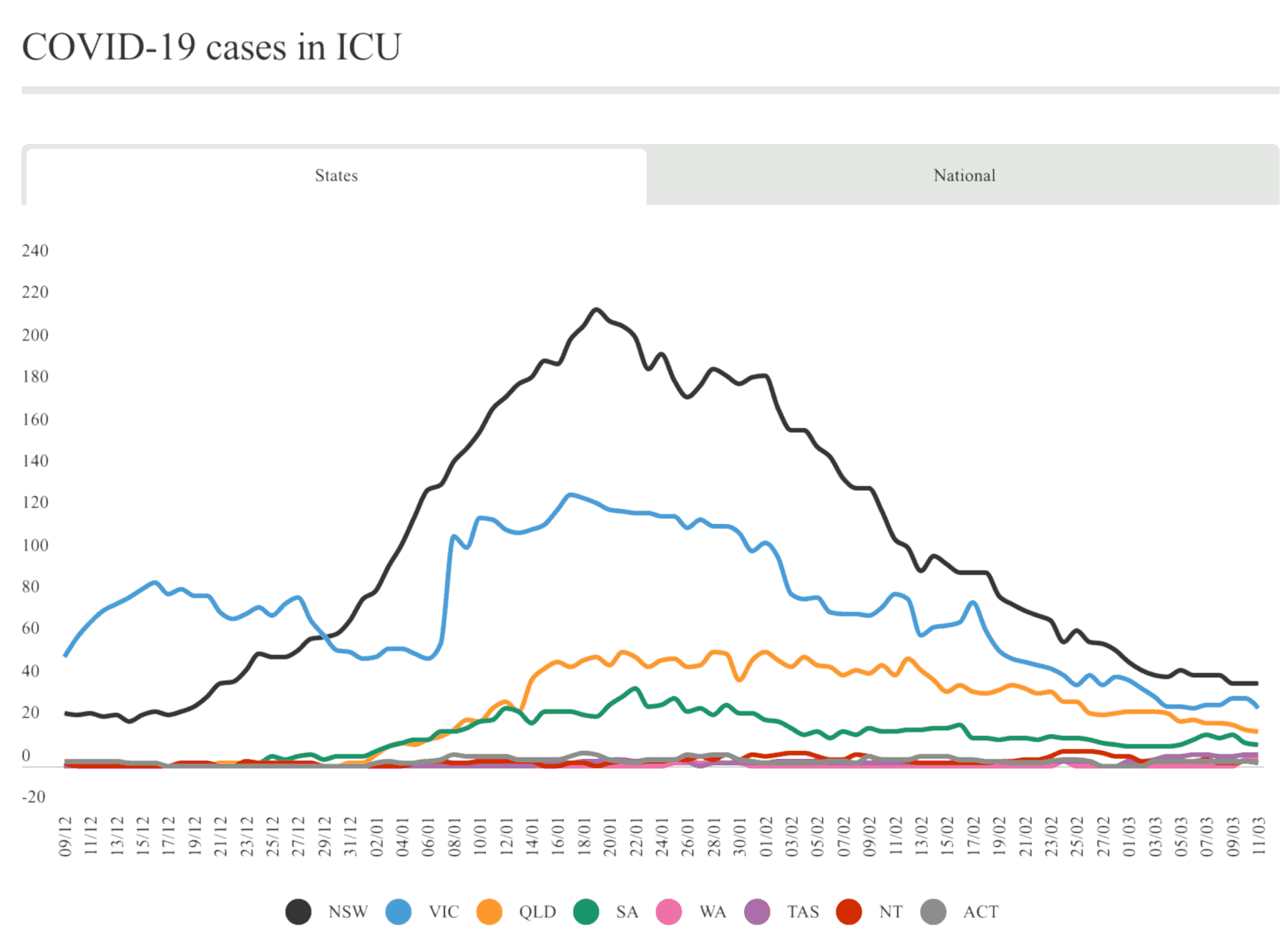

COVID-19 is going OK, as far as adverse outcomes go. Estimates of how many people here have COVID vary wildly, but it might be, say, 30% of the population. I have had it. Many of my friends have had it. Test positivity rates are increasing, but notably ICU rates are not, yet. Currently, approximately 0.0005% of the population is in the intensive care unit with it, and those people may or may not recover. Each of those cases is an individual human tragedy, of course, but also the scale of human tragedy is not large in population terms.

We have had 1975 deaths from COVID, overall compared to the scale of the everyday tragedy of mortality where 50,000 people die every year. That is much better than, e.g. cancer, which kills 14,000 people per year here..

The sun is shining this weekend for the first time in a month. I’m going to make hay.

5 References

Footnotes

It is complicated because Australia seems to be doing really well, but we are not very good at collecting or publishing data about particular variants, and we re-use the data of other countries that have a much lower vaccination rate but better variant tracking↩︎

That adventure in Indonesia, appearing at the OK Video festival with Sean Healy, was transformatively fun. I would have lost weeks from my life for it and counted that deal as good.↩︎