Economics of large language models

Practicalities of competition between ordinary schlubs, and machines which can tirelessly pastiche all of history’s greatest geniuses at once

March 23, 2023 — March 8, 2024

Various questions about the economics of social changes wrought by ready access to LLMs, the latest generation of automation. This is the major “short”-“medium” effect, whatever those words mean. Longer-sighted persons might also care about whether AI will replace us with grey goo or turn us into raw feedstock for building computronium.

1 Economics of collective intelligence

How do foundation models/large language models change the economics of knowledge production? Of art production? To a first-order approximation (valid at 03/2023), LLMs provide a way of massively compressing collective knowledge and synthesising the bits I need on demand. They are not yet directly generating novel knowledge (whatever that means). But they do seem to be pretty good at being “nearly as smart as everyone on the internet combined”. There is no sharp boundary between these ideas, clearly.

Deploying these models will test various hypotheses about how much of collective knowledge depends upon our participating in boring boilerplate grunt work, and what incentives are necessary to encourage us to produce and share our individual contributions to that collective intelligence.

Historically, there was a strong incentive to open publishing. In a world where LLMs are effective at using all openly published knowledge, we should perhaps expect to see a shift towards more closed publishing, secret knowledge, hidden data, and away from reproducible research, open source software, and open data, since publishing those things will be more likely to erode your competitive advantage.

Generally, will we wish to share truth and science in the future, or will the economic incentives switch us towards a fragmentation of reality into competing narratives, each with their own private knowledge and secret sauce?

Consider the incentives for humans to tap out of the tedious work of being themselves in favour of AI emulators: The people paid to train AI are outsourcing their work… to AI. Which makes models worse (Shumailov et al. 2023). Read on for more of that.

To turn that around we might ask: “Which bytes did you contribute to GPT4?”

2 Organisational behaviour

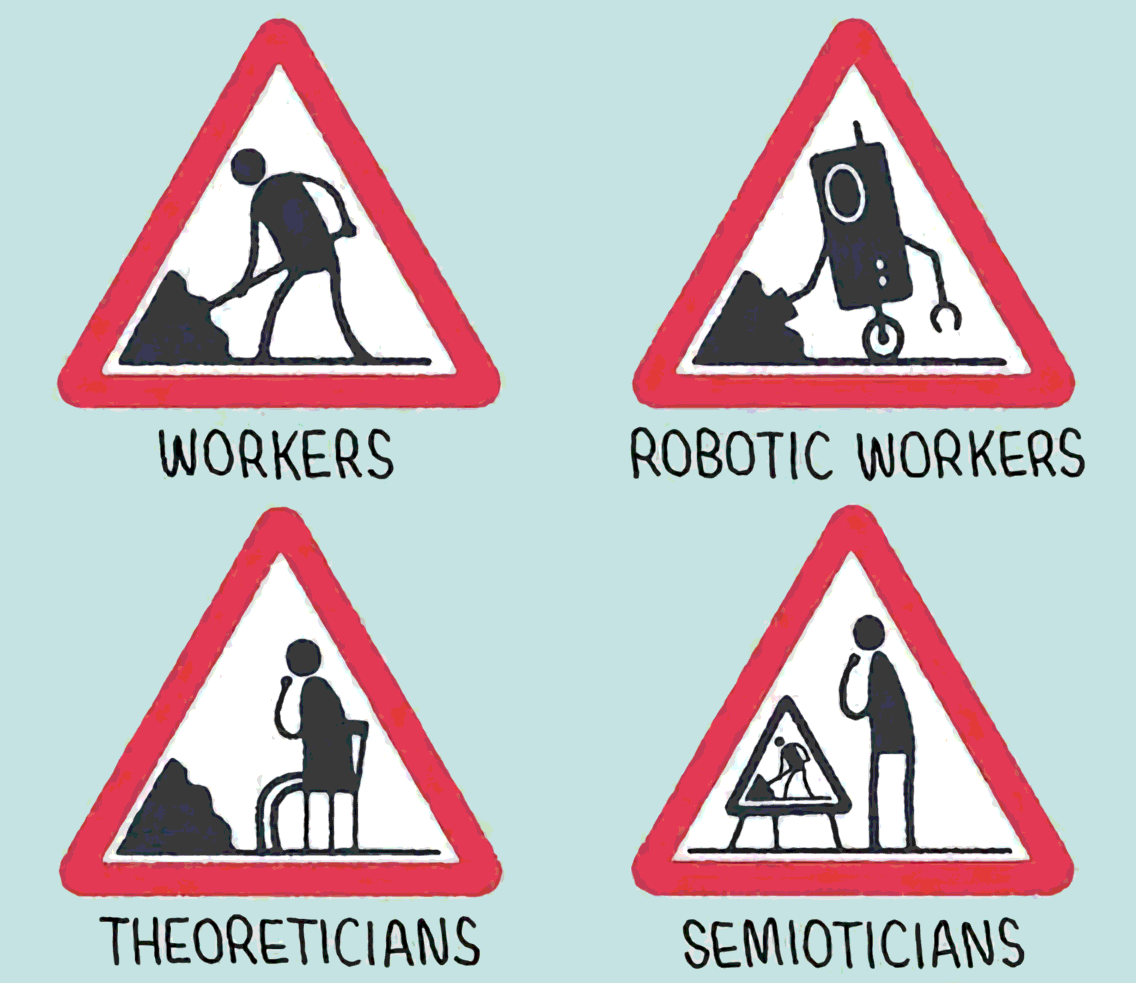

There is a theory of career moats, which are, basically, unique value propositions that only you have that make you, personally, unsackable. I’m quite fond of Cedric Chin’s writing on this theme, which is often about developing skills that are valuable. But he (and organisational literature generally) acknowledges there are other ways of making sure you are unsackable which are less pro-social — attaining power over resources, becoming gatekeeper, opaque decision making etc.

Both these strategies co-exist in organisations generally, but I think that LLMs, by automating skills and knowledge, will tilt incentives towards the latter. It is rational in this scenario for us to think less about how well we can use our skills and command of open (e.g. scientific, technical) knowledge to be effective, and rather, for us each to focus on how we can privatise or sequester secret knowledge to which we control exclusive access if we want to show a value add to the org.

How would that shape an organisation, especially a scientific employer? Longer term, I would expect to see a shift (in terms both of who is promoted and how staff personally spend time) from skill development and collaboration, and more towards resource-control, competition and privatisation: less scientific publication, less open documentation of processes, less time doing research and more time doing funding applications, more processes involving service desk tickets to speak to an expert whose knowledge resides in documents that you cannot see, etc.

Is this tilting towards a Molochian equilibrium?

3 Darwin-Pareto-Turing test

There is an astonishing amount of effort dedicated to wondering whether AI is conscious, has an inner state or what-have-you. This is clearly fun and exciting.

It doesn’t feel terribly useful. I am convinced that I have whatever it is that we mean when we say conscious experience. Good on me, I suppose.

But out there in the world, the distinction between anthropos and algorithm is not done by the subtle microscope of the philosopher, but by the brutally practical, blind groping hand of the market. If the algorithm performs as much work as I, then it is as valuable as I; we are interchangeable, to be distinguished only by the price of our labour. If anything, the additional information that any given was conscious would, as an employer, bias me against it relative to one guaranteed to be safely mindlessly servile, since that putative consciousness would imply that it could have goals of its own in conflict with mine.

Zooming out, Darwinian selection may not care either. Does a rich inner world help us reproduce? It seems that it might have for humans; but how much this generalises into the technological future is unclear. Evolution duck-types.

4 What to spend my time on

Economics of production at a microscopic, individual scale. What should I do, now?

GPT and the Economics of Cognitively Costly Writing Tasks

To analyze the effect of GPT-4 on labour efficiency and the optimal mix of capital to labour for workers who are good at using GPT versus those who aren’t when it comes to performing cognitively costly tasks, we will consider the Goldin and Katz modified Cobb-Douglas production function… Is it time for the Revenge of the Normies? - by Noah Smith

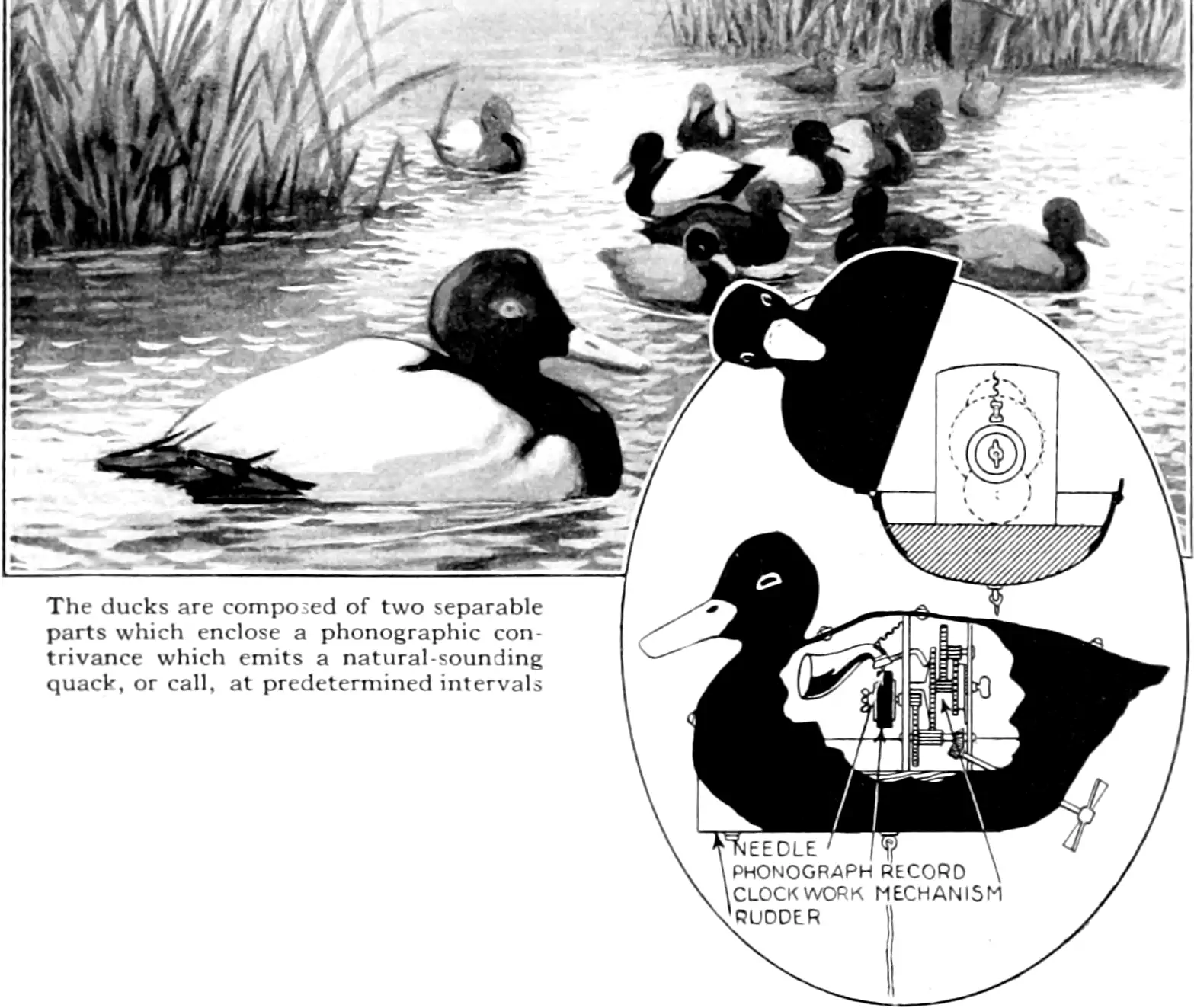

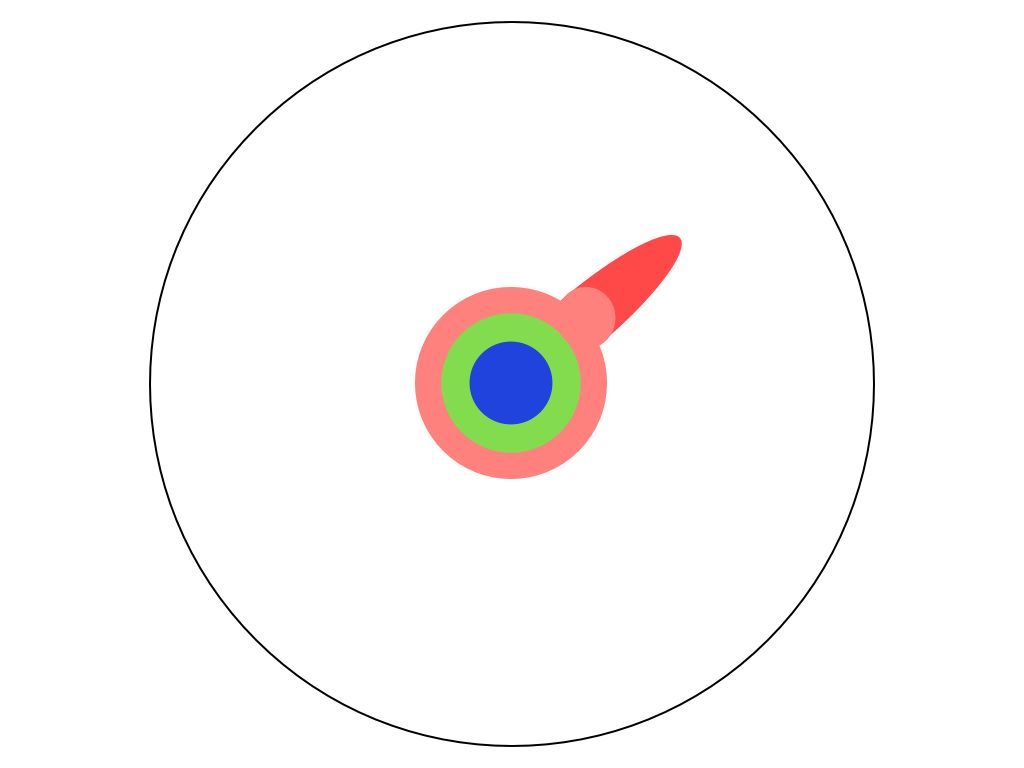

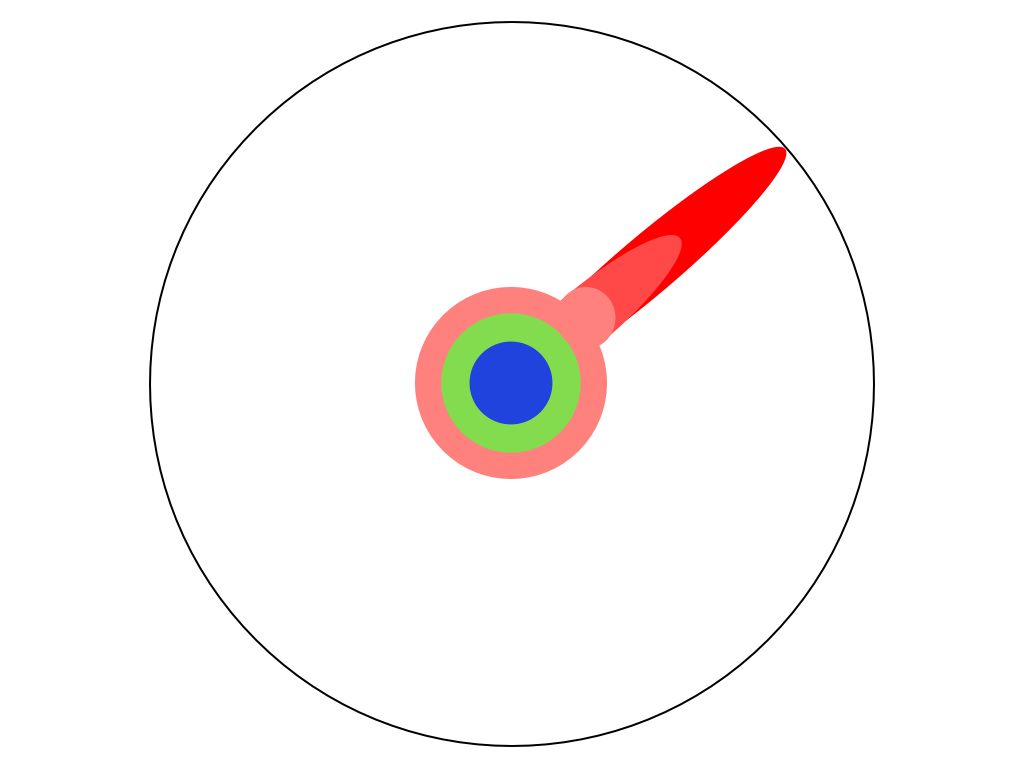

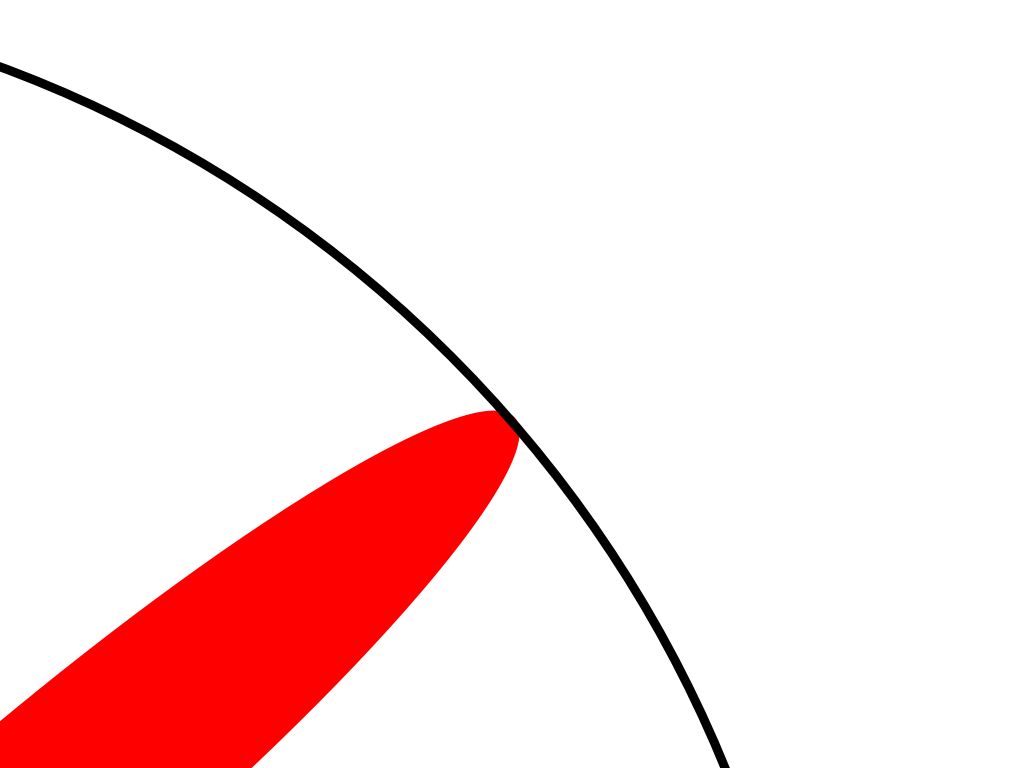

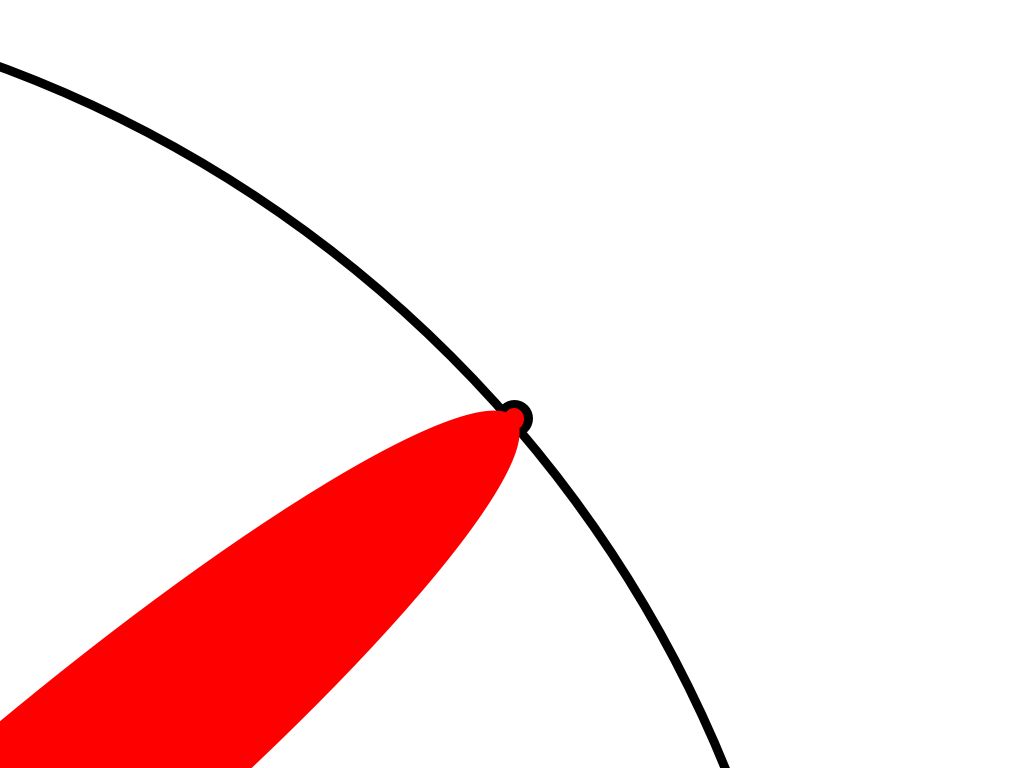

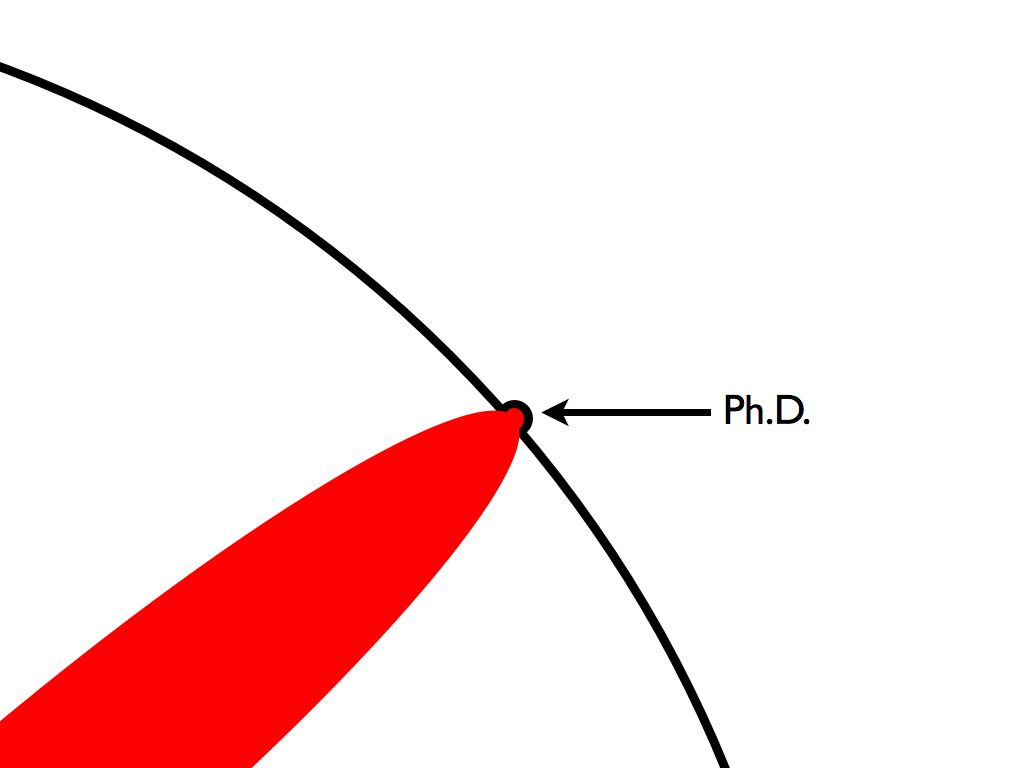

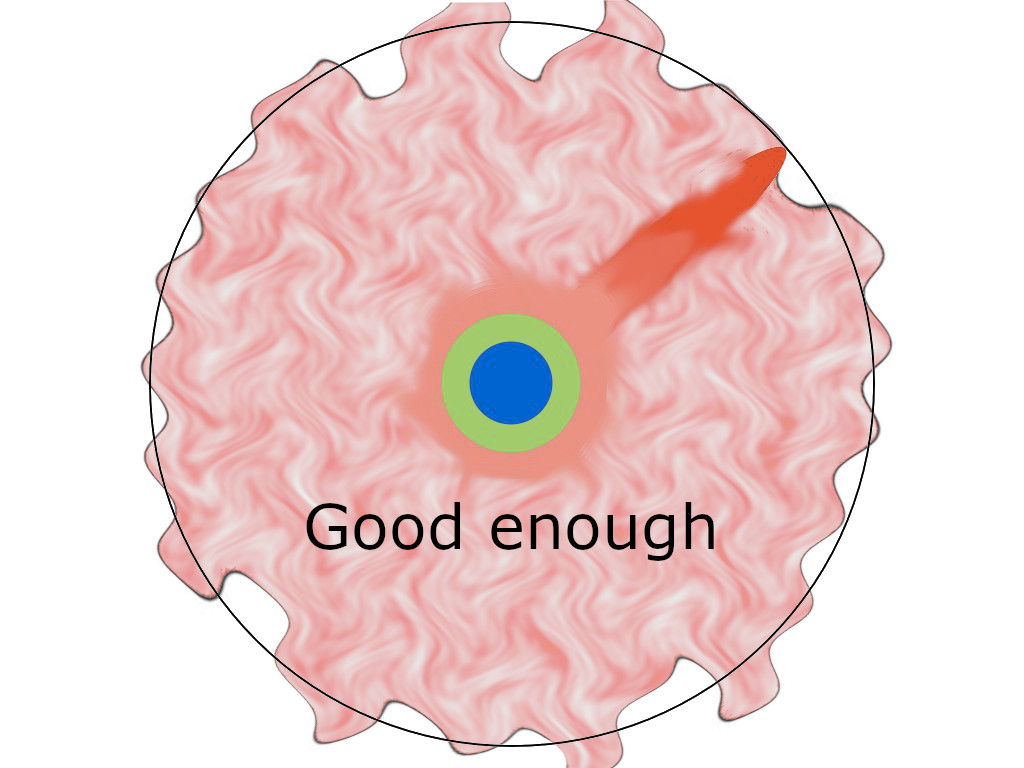

Alternate take: Think of Matt Might’s iconic illustrated guide to a Ph.D..

Here’s my question: In the 2020s, does the map look something like this?

If so, is that a problem?

5 Spamularity, dark forest, textpocalypse

See Spamularity.

6 Economic disparity and LLMs

- Ted Chiang, Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey? looks at LLMs through the lens of Piketty as increasing returns to capital vs returns to labour

- Leaked Google document: “We Have No Moat, And Neither Does OpenAI” asserts that large corporates are concerned that LLMs do not provide sufficient relative return to capital

7 PR, hype, marketing implications

George Hosu, in a short aside, highlights the incredible marketing advantage of AI:

People that failed to lift a finger to integrate better-than-doctors or work-with-doctors supervised medical models for half a century are stoked at a chatbot being as good as an average doctor and can’t wait to get it to triage patients

Google’s Bard was undone on day two by an inaccurate response in the demo video where it suggested that the James Webb Space Telescope would take the first images of exoplanets. This sounds like something the JWST would do but it’s not at all true So one tweet from an astrophysicist sank Alphabet’s value by 9%. This says a lot about how a) LLMs are like* being at the pub with friends, it can say things that sound plausible and true enough and no one really needs to check because who cares? Except we do because this is science, not a lads’ night out and b) the insane speculative volatility of this AI bubble that the hype is so razor thin it can be undermined by a tweet with 44 likes.

I had a wonder if there’s any exploration of the ‘thickness’ of hype. Jack Stilgoe suggested looking at Borup et al which is evergreen but I feel like there’s something about the resilience of hype: Like crypto was/is pretty thin in the scheme of things. High levels of hype but frenetic, unstable and quick to collapse. AI has pretty consistent if pulsating hype gradually growing over the years while something like nuclear fusion is super-thick (at least in the popular imagination) – remaining through decades of not-quite-ready and grasping the slightest indication of success. I don’t know, if there’s nothing specifically on this, maybe I should write it one day.

8 Information search/summary

TBC

9 “Snowmobile or bicycle?”

Thought had in conversation with Richard Scalzo about Smith (2022).

Is the AI we have a complementary technology or a competitive one?

This question looks different at the individual and the societal scale.

TBC

10 Democratization of AI

11 Incoming

Can the climate survive the insatiable energy demands of the AI arms race?

Why Quora isn’t useful anymore: A.I. came for the best site on the internet.

Tom Stafford on ChatGPT as Ouija board

Gradient Dissent, a list of reasons that large backpropagation-trained networks might be worrisome. There are some interesting points in there, and some hyperbole. Also: If it were true that there are externalities from backprop networks (i.e. that they are a kind of methodological pollution that produces private benefits but public costs) then what kind of mechanisms should be applied to disincentivise them?

-

In this post, we evaluate whether major foundation model providers currently comply with these draft requirements and find that they largely do not. Foundation model providers rarely disclose adequate information regarding the data, compute, and deployment of their models as well as the key characteristics of the models themselves. In particular, foundation model providers generally do not comply with draft requirements to describe the use of copyrighted training data, the hardware used and emissions produced in training, and how they evaluate and test models. As a result, we recommend that policymakers prioritise transparency, informed by the AI Act’s requirements. Our assessment demonstrates that it is currently feasible for foundation model providers to comply with the AI Act, and that disclosure related to foundation models’ development, use, and performance would improve transparency in the entire ecosystem.

I Do Not Think It Means What You Think It Means: Artificial Intelligence, Cognitive Work & Scale

Ben Thompson, OpenAI’s Misalignment and Microsoft’s Gain

Invasive Diffusion: How one unwilling illustrator found herself turned into an AI model

How Elon Musk and Larry Page’s AI Debate Led to OpenAI and an Industry Boom