Sharing / gig economy

Turking your ride

March 22, 2015 — November 21, 2019

Suspiciously similar content

McLaren D and Agyeman, J, 1025, Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities.

Satyajit Das’s The sharing economy creates a Dickensian world for workers gives historical perspective:

Academic researchers argue that the sharing or peer-to-peer platform is a new reinvention of an old model. Levels of self-employment were significantly higher in the US around 1900. Income was derived from selling labour or goods and services directly to customers. The retreat from formal employment, they argue, is positive, disintermediating corporations whose profit share of GDP has increased recently.

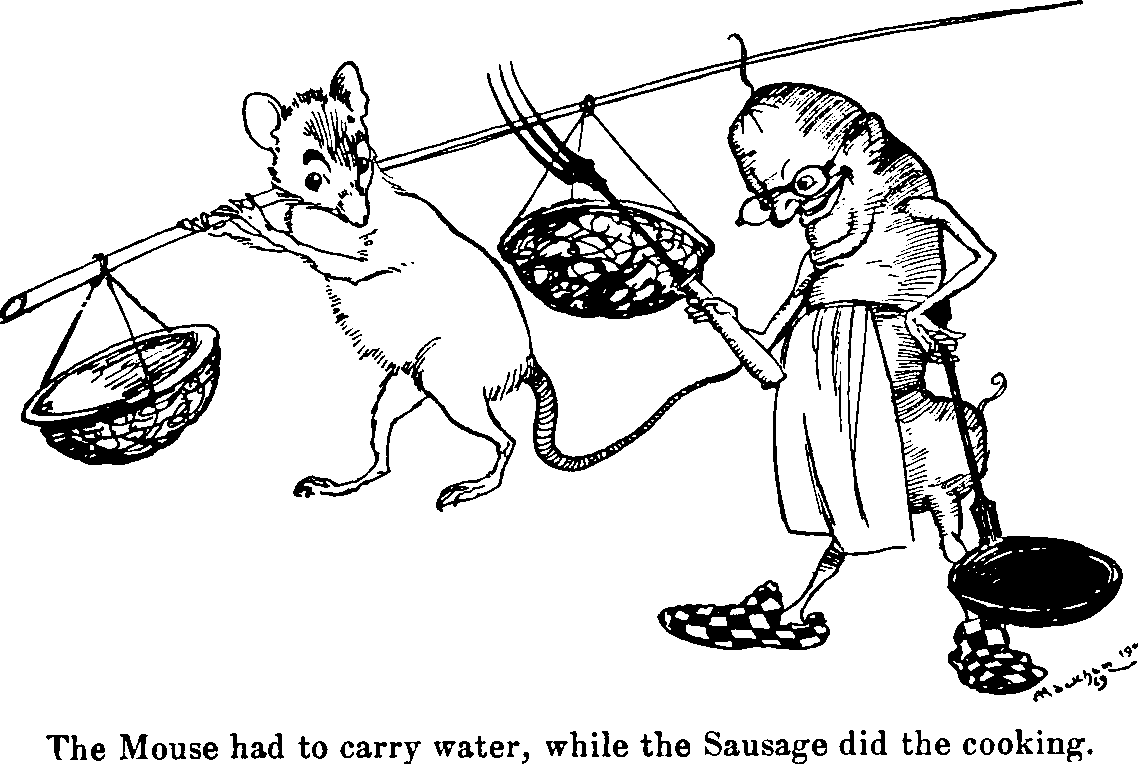

But the sharing economy reverses progress in labour markets. Whatever the gains from increased efficiency, it recreates a Dickensian world for a part of the population. Formal employment to varying degrees protects labour from exploitation and deprivation. The sharing economy transfers the risk of economic uncertainty from the employer to the employee with potentially tragic consequences.

Most importantly, the underlying economic premise is false. Consumption constitutes 60 to 70 per cent of activity in advanced economies. In 1914, Henry Ford doubled his workers’ pay from $2.34 to $5 per day, recognising that paying people more would enable them to afford the cars they were producing. Reduction of income levels and employment security ultimately reduces consumption and economic activity, impoverishing most within societies.

See neofeudalism for more on that.

Tom Slee/Whimsley does his thing: Some Obvious Things About Internet Reputation Systems

There is, however, one remaining difference between Airbnb and a traditional hospitality business. To go back to the beginning of this essay, sharing economy companies claim that it is both necessary and sufficient to solve problems of trust and coordination to unlock a large new economy of resource sharing. The “sufficient” part of this is valid only if there are no spill-over effects from the operations of the sharing economy, so sharing economies will campaign for freedom from those constraints that prevent them maximising their returns: health and safety standards, employment standards, licensing laws, and so on.

To be successful, the venture-capital-funded “sharing economy” will be forced to lose all those aspects of informal sharing that make “sharing” attractive, and to keep those aspects that erode neighbourhoods, erode employment rights, and remove basic standards. And if they succeed, they will have used the language of sharing to bring about an unregulated, free-market, neoliberal economy.

Second, the Internet is basically a communications medium, and communications is often not the main problem to be solved. Using power drills is not mainly about communications, it turns out it is mainly about convenience:

“For a drill, which by the way now costs $30, and you can get it on Amazon Now and have this thing delivered to you in an hour if you live in New York City — for something worth $30, is it really worth your time to trek potentially 25 minutes to go get something that you spent $15 to use for the day, and then have to trek back?” (Sarah Kesler)

Apparently he even wrote a book.

The place to start is with economist Ronald Coase’s famous theory of the firm. Coase pointed out, in his 1937 article “The Nature of the Firm,” that markets involve transaction costs […] Coase’s insight also helps explain why people own things, like power drills, rather than sharing them. A drill is a fairly inexpensive commodity. It’s easy to buy, it requires little maintenance, and it doesn’t take up much room in your house.

(But consider as a counter-example to the transaction-cost story here the possibility of a tool library. You’d check out the tool and return it, there’d be fines if you returned it in bad order, the librarians would make sure it was cleaned and charged, a sensible library would have multiple copies of common tools — and it would not be a single national-scale institution, but one at the level of a city or even a neighbourhood. Heck, consider the video rental store, which was a perfectly viable business until the bandwidth of home Internet exceeded the bandwidth of a tape or disc in a car.)

Another coined phrase: Internet turking:

An Internet turking company uses the following to expand into traditional industries:

- Internet economics— from global access to customers and workers via smartphones to massive economies of scale that drive costs down.

- An assembly line managed by a smartphone app. This is new. It’s Taylorism reworked for services. Workers micro-managed as if they were “bots”. It also sets the stage for rapid “botification” of work.

- Independent contractors who supply both capital (cars) and labour (driving); they take all of the risk.