Journalism, normative

Sensors for the superorganism

January 25, 2020 — June 22, 2023

Suspiciously similar content

Placeholder. I do not have time for this now and so will say little apart from bookmarking items for future return. I would like to have a better notion of what systems of incentives we might submit ourselves to in order to be able to make a better claim that our journalism is informing us about the world in the manner in which we need it. This is related to the parallel problem in academia of how peer review should work. In the expensive but essential task of verifying and prioritising news and events for public decision making, how can we make it happen the most efficiently? Can the profit centres be shifted, e.g. from raving social media conspiracy theory and pile-ons, to investigation and debate?

Here endeth the framing. Now cometh some content.

1 Business models

Derek Debus, The Death-Rattle of Journalism has a nice punchy explication which I would like to bookmark for its slightly macho posturing vibe. This tracks well with some people.

Yet it’s not just the rise of bad-faith shills of unreliable information that is to blame for this. It’s no secret newspapers are dying: facts are expensive, opinions are cheap. So media titans started pushing more and more op-eds and making it less and less clear that they were opinions and not news. The Media became less interested in publishing accurate information and more interested in getting that sweet, sweet ad revenue.

Nathan J. Robinson, The Truth Is Paywalled But The Lies Are Free

Ethan Zuckerman, The Case for Digital Public Infrastructure

Harnessing past successes in public broadcasting to build community-oriented digital tools

Not a complete solution, but there are some interesting ideas in scroll which bundles ad-less subscriptions to online media for readers. Scroll got bought by Twitter; it may appear as a Twitter feature I guess? There are various magazine bundling services out there, though. Here is a recent listicle.

Barry Schnitt has the easy job of complaining from the outside about Facebook (therefore anything he says is ambiguously ‘concern trolling’), but his descriptions of the incentives are tidy.

It has been said that a lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to put its pants on. Now, Facebook’s speed and reach make it more like a lie circles the globe a thousand times before the truth is even awake. This is no accident. Ironically, the one true conspiracy theory appears to be that malevolent nation-states, short-sighted politicians, and misguided interest groups are using conspiracy theories to deliberately misinform the public as a means of accomplishing their long-term strategic goals. The same could be said for those deliberately using incendiary and divisive language, which is similarly allowed to propagate your system.

Unfortunately, I do not think it is a coincidence that the choices Facebook makes are the ones that allow the most content— the fuel for the Facebook engine— to remain in the system. I do not think it is a coincidence that Facebook’s choices align with the ones that require the least amount of resources, and the choices that outsource important aspects to third parties. I do not think it is a coincidence that Facebook’s choices appease those in power who have made misinformation, blatant racism, and inciting violence part of their platform. Facebook says, and may even believe, that it is on the side of free speech. In fact, it has put itself on the side of profit and cowardice.

2 Journalism and expertise

Hardcore evidential data journalism is hard to write and hard to read.

Miller (2013) is one guide to how to do it responsibly.

But is responsibility enough in an increasingly specialised world? How about in an increasingly distrustful world?

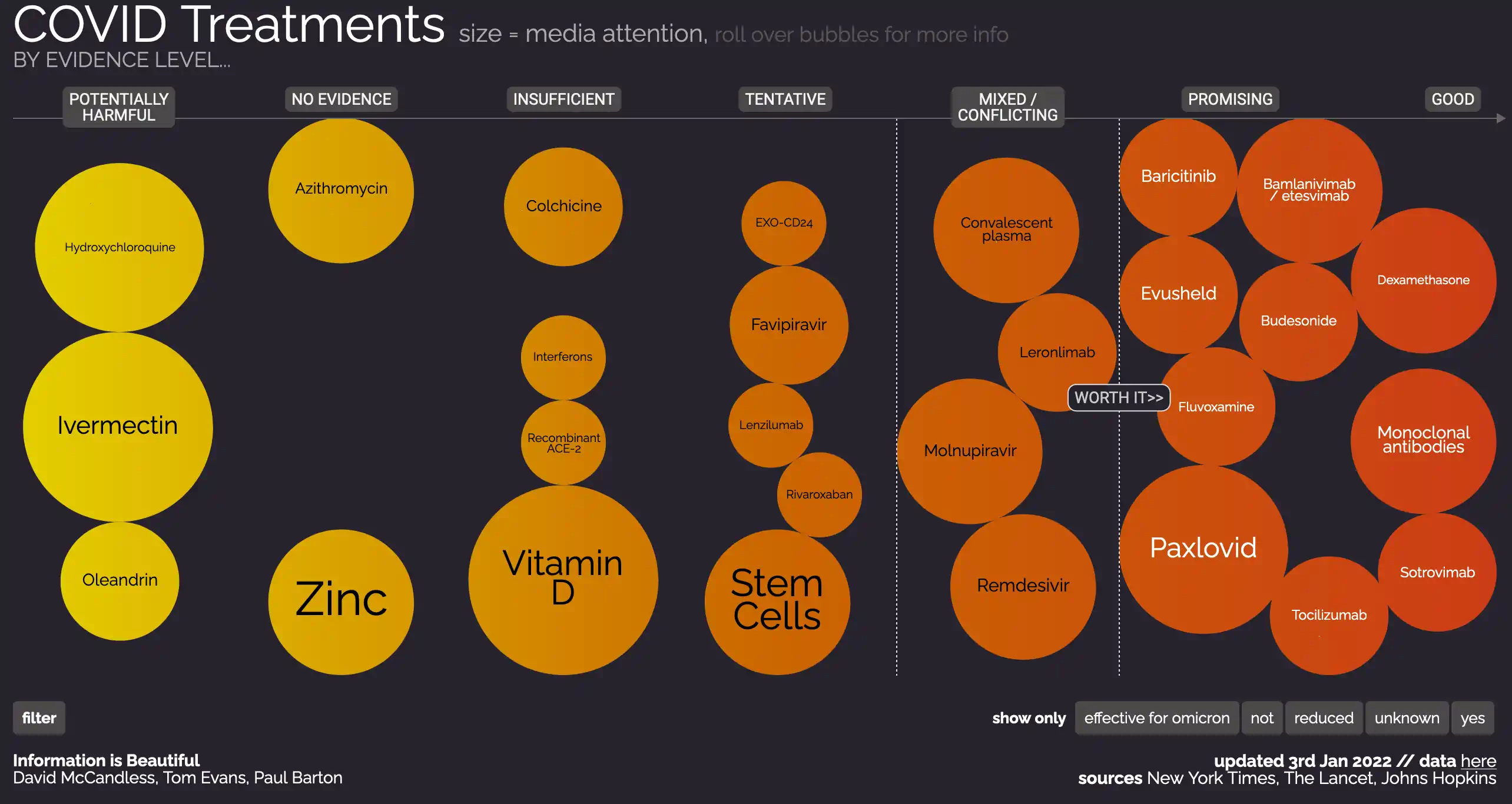

See the Astral Codex Ten Ivermectin post mortem which tears apart the data journalism on ivmmeta.com, and immaculate and information-dense report on what happens Ivermectin. Except the ivmmeta methodology is not great because they include suspect studies and conflate different measurements.

Most journalists are not qualified to either write the site or rebut the site. Who is going to do this? Who is going to demand this?

The latest case study in media analysis is the COVID-19 media response. This was especially maladaptive in the USA I am told. Adam Elkus, The Fish rots from the head:

It is an exaggeration to say that fringe weirdos on social media often were more well-informed than people that exclusively evaluated mainstream sources, but not that much of an exaggeration as most would think. And that is not accidental. As Ben Thompson noted, the global COVID-19 response depended on an enormous amount of information developed and shared often in defiance of traditional media (which underrated and even mocked concern about the crisis) and even the Center for Disease Control (which attempted to suppress the critical Seattle Flu Study). The response still depends primarily on transnational networks and often must operate around rather than through official channels.

Taken together, all of this is astounding in both its scope and simultaneity. And it makes a mockery out of the cottage industry developed over the last few years to preserve our collective epistemic health.

Analysts obsessed for years and years over the threat of Russian bots and trolls and Macedonian teenagers to democratic institutions and public life, arguing that misinformation and propaganda spread via social networks would perturb the very fabric of reality and destroy the trust and cohesion necessary for liberal democracy to survive. This concern was responsive to the surface elements of deeper psychological and cultural changes, but it often was hindered by its emphasis on top-down control of computational platforms that eluded control at subjectively appropriate cost. Nonetheless, reasonable people could disagree about the response to the problem but not the actual implicit diagnosis. The diagnosis being that the unraveling of legacy institutions and their capacity to enforce at least the fiction of consensus over underlying facts and values about democratic authority was dangerous and no effort should be spared to fight it.

But as we have seen, these institutions are perfectly capable of unraveling themselves without much help from Russian bots and trolls and Macedonian teenagers. And if the fish rots from the head, then the counter-disinformation effort becomes actively harmful. It seeks to gentrify information networks that could offer layers of redundancy in the face of failures from legacy institutions. It is reliant on blunt and context-indifferent collections of bureaucratic and mechanical tools to do so. It leaves us with a situation in which complicated computer programs on enormous systems and overworked and overburdened human moderators censor information if it runs afoul of generalized filters but malicious politicians and malfunctioning institutions can circulate misleading or outright false information unimpeded. And as large content platforms are being instrumentalized by these same political and institutional entities to combat “fraud and misinformation,” this basic contradiction will continue to be heightened.

3 Trust systems

Jonathan Stray, What tools do we have to combat disinformation?

Lead Stories uses the Trendolizer™ engine to detect the most trending stories from known fake news, satire and prank websites and tries to debunk them as fast as possible.

(I think this is publicity/loss leader for Trendolizer, a media buzz product.)

Maybe see trust machines?

4 Information economics

Why it’s so hard to fix the information ecosystem

Some people may spread misinformation as a hobby or a political signalling device, but many people are doing it for personal gain. Antivaxxers have blogs and podcasts to promote. Propagandists serve their nation or movement. Corporate shills are collecting a salary, academic frauds get tenure, and so on. For all of these actors, spreading misinformation is a job rather than a hobby. It confers direct financial and/or reputational benefit.

Debunking misinformation, on the other hand, benefits far more people than the debunker. If you go on Twitter and convince 1000 people that vaccines are OK, you might save a life, but you won’t get paid for it. If a greedy corporation lies about its carcinogenic products, and you go around posting evidence against their lies, and people stop using the products as a result, you still won’t be the main beneficiary. In economics jargon, much of the benefit of debunking misinformation is external — it accrues not to you, but to the innocent bystanders whom you save from being misled.

As any economist knows, this is a big problem. Public goods—or anything with a positive externality attached to it—tend to be underprovided. Because there just aren’t that many incentives in place to combat misinformation, people will tend to do it just as a hobby. That will tilt the balance in favour of the misinformers, some of whom are doing it as a job.

5 Crypto and journalism somehow

The (now defunct) Civil tried some exotic cryptocurrency-based options here.

We build tools to help readers discover and support trusted journalists around the world on a decentralized platform.

One of these tools was a blockchain instrument to publish, preserve and… judge(?) journalists. The explanation of how that latter part was supposed to work was never clear to me and I meant to look into it but they folded before I did.

Erasurebay comes from the other direction with respect to blockchainery. They are a blockchain company who wants to move into information brokerage business. Their explanation is characteristically abstruse nerdview so I can’t imagine this going far until they hire someone with a communications degree to produce comprehensible prose for them.

6 Activist short sellers

Short selling: How tiny ‘activist’ firms became the sheriffs in the stock market’s Wild West

Short-selling firms like Hindenburg Research, Viceroy Research, and Muddy Waters have earned outsize attention—and big windfalls—by shining a harsh light on overhyped companies.

Stock vigilante wins by exposing company frauds, Invest News & Top Stories

Founded in 2017, Hindenburg specialises in publishing detailed reports about publicly traded companies, poking holes in their stories and alerting investors to potential malfeasance. The boom in special purpose acquisition companies has provided Hindenburg with fertile ground.

It is not an act of public service. Hindenburg, which has the backing of several investors, also makes financial bets that the stocks of the companies Mr Anderson targets will fall after the firm issues its research. When the stocks do fall, Hindenburg makes its money in what is called a “short” trade.

It is easy to find things to like about this model. And also easy to imagine it descending into infowars.

Short & distort? The ugly war between CEOs and activist critics. Farrell

7 Mechanism design for journalism

7.1 Mechanisms which reward audience diversity might help

Researchers find new way to amplify trustworthy news content on social media without shielding bias, summarising Bhadani et al. (2022), argues that mechanisms that reward cross-partisan engagement rather than just engagement can improve trustworthiness of media.

7.2 Journalism markets

Use Prediction Markets To Fund Investigative Reporting:

Hindenburg Research has a great business model:

- Investigate companies

- …until they find one that is committing fraud

- Short the fraudulent company

- Publicly reveal the fraud

- Company’s stock goes down

- Profit!

This is indeed interesting. Although a cost-benefit analysis of finding actual fraud versus accusing them of fraud and shorting them anyway would need to be done before I backed such a business. Also, if you had a business that weaponized baseless fraud accusations, I might be able to sell that service to competitors for some extra cash flow.

8 Slate star codex kerfuffle

Would you like an interesting core sample of current media dynamics? Try the Slate Star Codex kerfuffle, which is an interesting case study.

9 Interesting attempts

9.1 The blogosphere

Better than even, except possibly for people who are not me.

9.2 Undark

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent digital magazine exploring the intersection of science and society. It is published with generous funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, through its Knight Science Journalism Fellowship Program in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

A recent scandal involving Undark shows why independent journalism is not enough; accountable journalism is required.

9.3 Weeklypedia

The WEEKLYPEDIA links to whatever Wikipedia articles were mostly hotly edited/contested this week. Well, that is an interesting mechanism for sorting, at least.

10 Incoming

An Insider’s Guide to “Anti-Disinformation”

An interesting read. I’m not sold on the framing of the “censorship industrial complex” part;

…anyone taking military, defence contractor, or intelligence agency money should not be part of civil society and human rights events. […] the list is long. As the database of “anti-disinformation” groups and their funders develops there will be more to add.

It implies agencies that are too good at enacting their coordinated agenda in amorphous civil society; in my experience, orgs have a hard time enacting an agenda in their own ranks, let alone being a competent patsy for someone else.

Further, a story’s truth is independent of its provenance; state actors and Substack newsletter authors may both lie, or be mistaken.

If we want news systems that provide more truth, then it needs to come about by improved mechanisms for verification and cross-checking. I’m not mightily persuaded that targeting the Anti-Disinformation Agenda (or the Gay Agenda, or Big Pharma or Anti-vax Agenda or the Censorship-Industrial complex in any given nation state, or any of the other Agendas and shadowy elite coordination games) gets us any closer to that. If there are organised and opposing interests then that is useful to know, but it is neither necessary nor sufficient to get us a functional truth-seeking media.

The righteous hot takes about How Our Agenda Is The Correct One DO get me liking and subscribing to newsletters that fulminate about censorship. But am I thereby playing into the Anti-Anti-Disinformation Agenda?

As Local News Dies, a Pay-for-Play Network Rises in Its Place

Orthographic media. Great metaphor: “once again found myself sucked into a far-off event that truly does not matter, and it occurred to me that social media is an orthographic camera.”

Matthew Yglesias, What I learned co-founding Vox

The New Atlantis, How Stewart Made Tucker

Deciphering clues in a news article to understand how it was reported