Medicalisation

January 27, 2020 — October 21, 2024

Suspiciously similar content

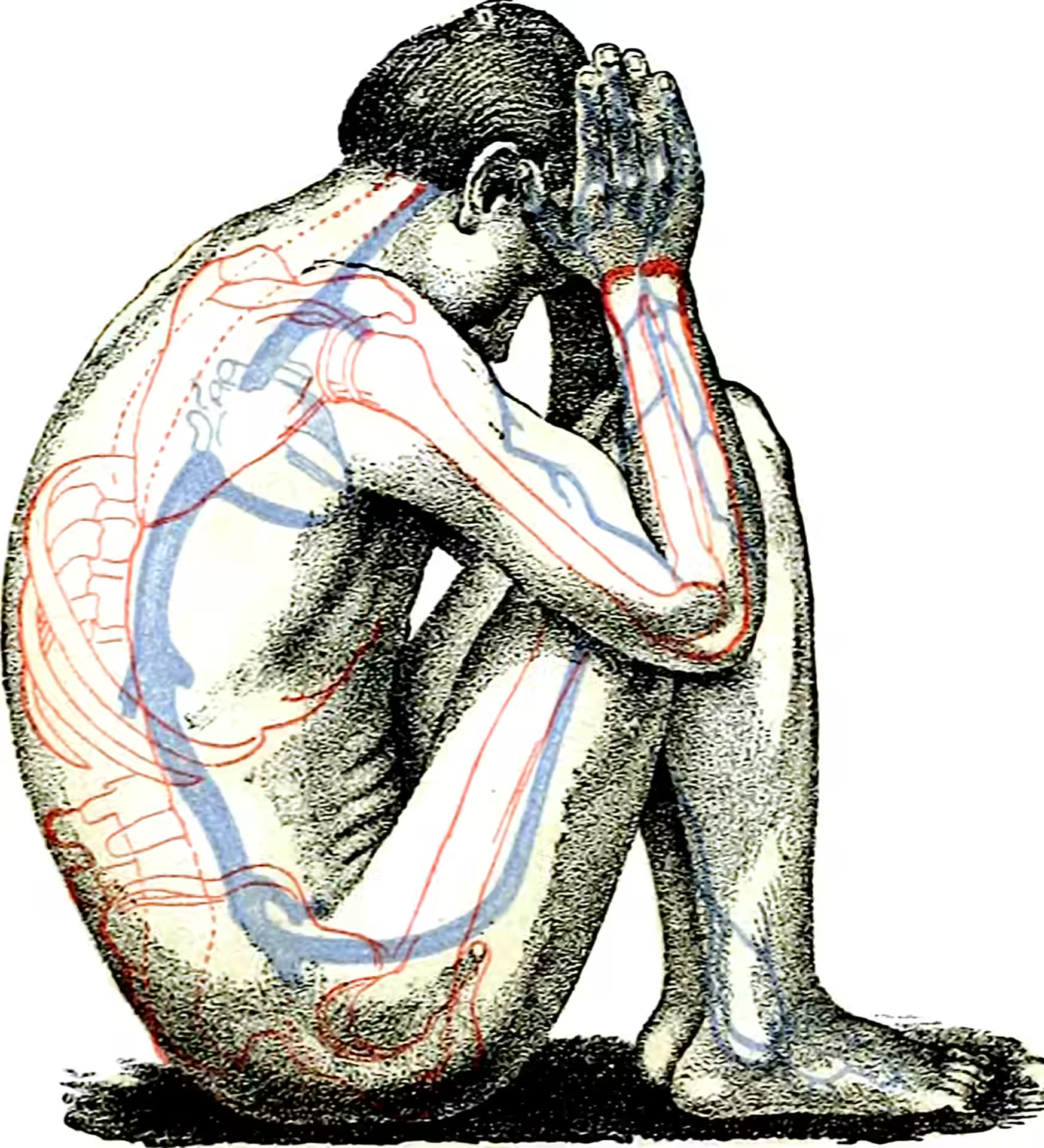

Stub. On the mechanics and political economy of calling phenomena diseases, versus other classifications.

Contested questions: Are the following phenomena best regarded through the lense of disease, or not? ADHD? depression? cognitive enhancement by nootropics? Personality disorders Transgender identities Sexual orientation? General weirdness? Treating things, even parts of things, as medical conditions can be stigmatising. But also, observationally speaking, it can motivate the apparatus of society to treat them. What are the trade-offs here? When is something best treated as a disease, and when as… something unremarkable? Or as a moral failing, which must be punished?

One alternative seems to be classifying these states as moral failings, which rarely seems helpful. Are there universal principles we can find for this, or merely contingent attempts to solve for marginal improvements to the status quo?

Why does classifying something as a disease make it more legitimate to treat it, whereas mere need to thrive does not? What are the status effects of calling something an illness versus a preference? I’m curious about the interaction with the great society, making disease legible and thus implicating it in e.g. the health care system.

1 Incoming

Sam Atis, in More notes on ADHD, connects ADHD medication to nootropics and finds no meaningful differentiation.

Lionel Shriver compares transgenderism to anorexia. Because gender identity is an especially fraught topic I will flag that I disagree with her conclusion, but she does some interesting work there.

-

[…]this is a newsletter where I write about disability and capitalism, covering the politics of mental health, the history of popular psychology, and the philosophies of living outside the norm.

Iatrogenesis on Illich (1975):

… at another level social iatrogenesis is the medicalisation of life in which medical professionals, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device companies have a vested interest in sponsoring sickness by creating unrealistic health demands that require more treatments or treating non-diseases that are part of the normal human experience, such as age-related declines. In this way, aspects of medical practice and medical industries can produce social harm in which society members ultimately become less healthy or excessively dependent on institutional care. He argued that medical education of physicians contributes to medicalisation of society because they are trained predominantly for diagnosing and treating illness, therefore they focus on disease rather than on health. Iatrogenic poverty (above) can be considered a specific manifestation of social iatrogenesis.