Ethical consumption

Veganisms, boycotts and other individual solutions to structural problems

February 5, 2020 — April 7, 2024

Suspiciously similar content

Can buying products strategically be an effective way to improve the outcomes I care about in the world? An interesting meeting point of applied moral philosophy and economics.

What kind of cost-effectiveness can we expect from this intervention?

tl;dr I am generally skeptical of the ROI of ethical consumption and would start trying to make the world better in one of the many other ways I can do so. However, this is not to say that ethical consumption is pointless; nor that it is harmful if it does not displace those other higher-ROI activities. However, ethical consumption is hard to evaluate in terms of net good (“does it actual solve the problems?”), and does have downsides, so I do not think it would be wise to spend too much effort on it.

I do some ethical consumption (I try to consume low-carbon things, buy second-hand etc, not eat food with a high carbon footprint) but try to avoid letting my ethical consumption habit get too complicated, as apparently-ethical-consumption can, observationally, easily become a selfish choice to feel good rather than do good. Or an obsessive hobby which is no longer closely coupled to the problem it purports to solve (have you ever seen someone acquire an unaffordable organic food habit?) Or, it can become instrumental in someone else’s propaganda campaign. Related: Meadows (1999).

Connection: Faking it until you make it, or just faking it?.

1 Systemic solutions

If a thing, X, has some unwanted side effects, a society can try to reduce it by systemic solutions.

A classic one here, which I generally favour, is taxing it. This would reduce the amount of that product and thereby its damage, then use the tax income to, e.g. repair the damage. This seems like a higher-yield idea than relying on conscientious objectors to opt out, and it is a subtle and flexible instrument, allowing us to trade degrees of harm by price signals. Price signals might not be perfect, but they are better than guessing. Also, why not tax harmful stuff, like pollution? It seems better to tax that than to tax good things, like income.

Institutionally, taxes have the useful quality that can pay for themselves. The Bureau of Taxing X will have jobs and staff and a budget and will be incentivised to keep taxing X. That is, if X is truly harmful then controlling X may as well have a business model that keeps institutional on the side of justice.

Alternatively, we could ban things. This is frequently not as efficient because even very harmful things can be sufficiently useful to merit the harm sometimes. If we ban some product, then fewer institutions will directly benefit from the ban (although bureaucratic inertia might), but people who might be able to value capture from lifting the ban will have incentive to lobby against it.

Both of these are systemic solutions. What if our society doesn’t have the attention or will to systemically regulate something which you feel is harmful? That is when we consider individual solutions like ethical consumption.

2 Limits to direct consumer effects

Much of the bad stuff happening to the world is remote from immediate consumer demand. Any strategy which required the whole world to be neurotic middle-class people prepared to spend too much time googling environmental impacts is not a plausible strategy to fix the problem in itself.

Also, deciding the ethical option is hard. Did that Sodastream boycott help anyone in the Palestine-Israel conflict?

3 Goodharting

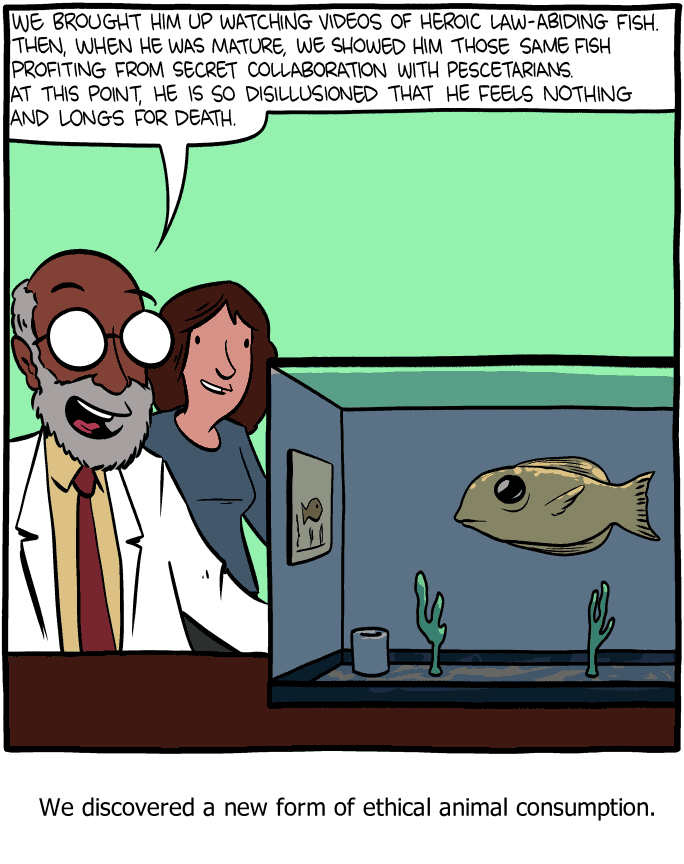

If our target is societal improvement in terms of animal cruelty, or lower carbon footprint or something, and we decide to measure progress towards that by individual metrics such as “number of animal products consumed”, then we have a Goodhart problem.

4 Size of effects

5 Recruiting versus alienating consumers

Are my consumption choices going to spread to wider society, or lead to alienating potential recruits by making it look sanctimonious? The latter risks making ethical consumption counter-productive even if the product you have chosen is the most immaculately ethical choice in itself. Attempts to make the world better can play into signalling dynamics, tribalism and various other annoying debilities of modern society such as invasive arguments.

6 Generating blame

Perhaps by making people morally responsible for consumption we are making some choices blameful, which makes them easier to maintain.

7 Jevons effects

What if my campaign to use less of a thing makes it cheaper, increasing consumption by others? TBC

8 Food in particular

9 Asymmetries

TBD.

There are various asymmetries in ethical consumption. In The Most Intolerant Wins Taleb talks about the advantageous leverage of veganism.

From the other direction, if I make a choice to consume less of a thing, that probably means that I believe it is over-consumed by virtue of being too cheap. Which means that it is probably also cheap for other people to “undo” my ethical consumption.

10 Pump-priming

TBD

11 Movement-building

TBD

12 Offsetting

Robust egg offsetting: A great discussion to have over dinner as you mop up the foie gras and ortolan.

It is hard to explain the experience of reading this, but I recommend having that experience. There is some interesting consideration of mechanism design in there, and some unusual assumptions. I wonder how to rustle up the required philanthropists (philornithists?) to seed the scheme with egg offset certificates?

Also, an unusual moral philosophy backs this:

Most interventions consist in lobbying or advocacy, trying to convince other people to pay a cost (e.g. to eat less meat or to pay for better animal welfare standards). I think that’s ethically problematic as an offsetting strategy relative to paying the cost yourself…

I take issue with most parts of that paragraph for reasons we can unpack if there is time.

Anyway, the essay is worth reading. An excellent pairing with David G and Froolow’s essay, Is Eating Meat A Net Harm?.

13 Incoming

Connor Tabarrok, Longtermism v.s. veganism: Pick one

Elizabeth Van Nostrand and Tristan Williams, Emotional sustainability of hardline veganism versus reducitarianism:

I think it’s really hard to draw a line in the sand that isn’t veganism that stays stable over time. For those who’ve reverted, I’ve seen time and again a slow path back, one where it starts with the less bad items, cheese is quite frequent, and then naturally over time one thing after another is added to the point that most wind up in some sort of reducetarian state where they’re maybe 80% back to normal (I also want to note here, I’m so glad for any change, and I cast no stones at anyone trying their best to change). And I guess maybe at some point it stops being a moral thing, or becomes some really watered down moral thing like how much people consider the environment when booking a plane ticket.

I don’t know if this helps make it clear, but it’s like how most people feel about harm to younger kids. When it comes to just about any serious harm to younger kids, people are generally against it, like super against it, a feeling of deep caring that to me seems to be one of the strongest sentiments shared by humans universally. People will give you some reasons for this i.e. “they are helpless and we are in a position of responsibility to help them” but really it seems to ground pretty quickly in a sentiment of “it’s just bad”.

To have this sort of love, this commitment to preventing suffering, with animals to me means pretty much just drawing the line at sentient beings and trying to cultivate a basic sense that they matter and that “it’s just bad” to eat them.

Interestingly explicit example of the what to taboo problem.