Remix and copyright

October 29, 2014 — August 21, 2023

Suspiciously similar content

“Everything is a remix”. The artistic kind of intellectual property Dem bow, Amen break. Soundclash. Versioning. Detournement. Culture jamming. How to monetize your music.

-

The music industry got exactly what it wished for: a world in which the customary borrowing and trading between musicians and their songs was prohibited, with incredibly stiff penalties. To the extent that they’d even considered that this would interfere with normal musical activity, they’d assumed that it wouldn’t interfere with their activities, since the three labels would be able to cross-license to one another, and between them, they’d own everything.

But they didn’t think it through. They failed to realize that the legal liability regimes they’d created would cut both ways, and that the peripheral acts and businesses—obscure Christian hiphop artists, say—would see the giant labels and their stars as irresistibly juicy targets.

They were the proverbial dog that finally caught the bus, and then had no idea what to do with it.

Yglesias finds a free speech angle in Oh, the intellectual property rights you’ll extend

Fascinating edge cases are multiplying: Do AI algorithms create their own work, or is it the humans behind them? What happens if AI software trained solely on Beyoncé creates a track that sounds just like her?

Youtube creators charging themselves with copyright breach

Jon Caramanica argues Pop music isn’t made in a vacuum. Copying isn’t always bad. And a new trend pulling more pop stars into courtrooms is a dangerous one.

In hip-hop especially, artists frequently incorporate fragments of earlier songs as a kind of wink, or nod to a forebear. But depending who’s doing the nodding, it doesn’t always go smoothly. In 2014, Drake revisited lyrics by the Bay Area hip-hop elder Rappin’ 4-Tay, who, unimpressed, chose to publicly invoice Drake for $100,000.…

The idea that there is a determinable origin point where a sonic idea was born is a romantic one. But a song is much more than romance these days — it is an asset, and a perpetual one at that. Note the recent boom market in the rights to song royalties. Check out the listings on royaltyexchange.com, where you can bid on fractional ownership to the rights for thousands of songs. …A fractional claim (via songwriting or sample credit) on a pop megahit can mean millions of dollars.

This system encourages bad-faith, long-shot action.

If echoing is always going to be treated as thievery, then songwriting credits and payments should be trickling back way past the 1970s and 1980s, all the way back to Robert Johnson and the Carter Family and Chuck Berry and the Last Poets — perpetual royalties for foundational innovations.

Allthemusic is every possible 8-note, 12-beat melody released into the public domain. Making 68+ billion melodies, 2.6 terabytes of data. there is an accompanying Ted talk by creator Damien Riehl, and a Recs summary.

Larry Lessig

Theft: a history of music tell this tale in comic book form

Johannes Kreidler trolls GEMA:

If you want to register a song at GEMA (RIAA, ASCAP of Germany) you have to fill in a form for each sample you use, even the tiniest bit.

On 12 Sept 08, German Avantgarde musician Johannes Kreidler registered — as a live performance event — a short musical work that contains 70,200 quotations with GEMA using 70,200 forms.

Melancholy Elephants, Spider Robinson’s 1982 short story about the copyright creative singularity

Sigur Rós tried not to sell out, and got sold out: homage or fromage? (innblástur eða stuldur?)

We’re not suggesting anyone’s ripping anyone off here, or has purposely gone out to plagiarise sigur rós music, because that might get us sued (which would be ironic). and in any case, you can get all the musicologists’ reports you like and all they will tell you is that the chord sequence is “commonly used” or the structure is a “style-a-like” and not a “pass off” rós. or — in this case — that despite the fact that the two pieces are “strongly similar in terms of general musical style, instrumentation and structure” and “created with a knowledge of and/or reference to the works of sigur rós in general and ‘hoppipolla’ in particular”, there is “insufficient evidence in the music to support a claim for infringement of the copyright”. in other words change a note here, swap things around a bit there and, hey presto, it’s an original composition. inspiration moves in mysterious ways.

How to Copy a Song: A Handy Primer

Recycling is a fundamental part of the song creation process. The trick is distinguishing the difference between good copying (legal, inspired) and bad copying (illegal, shameless). To figure out how to copy a song, you must first know which parts to copy.

-

If you haven’t heard it yet, I finally cooked down a Zunguzung Mega Mix that features all 50+ instances that have come to my attention since I first started listening for that catchy likkle tune and, with the publication of this piece back in 2007, enlisting others to lend me their ears.

-

This is our attempt to survey the damage, assess the gains, and try to put the mp3’s first full decade in perspective. Keep in mind that while the mp3 is a radically new technology, it’s not a different musical medium: The mp3 is still “recorded music” — that’s not going to change until Apple unveils the iBrain — but it’s recorded music that moves around very differently than ever before. As a result, mp3s have opened up vast new musical horizons over the past 10 years — how we discover it, the value we give to it, and how we see ourselves connected to other people through it — that both depart from and build upon the innovations that came before it. Everything’s still messy at the moment, but it’s not going to be this way forever — a few decades from now, we’ll most likely find ourselves nostalgic for the mp3 decade.

Oops, copyright even prevents us from following the laws we just made

No copyright — the real reason for Germany’s industrial expansion?.

Long bow that has not managed to pass peer review, but an entertaining long bow:

Höffner has researched that early heyday of printed material in Germany and reached a surprising conclusion — unlike neighbouring England and France, Germany experienced an unparalleled explosion of knowledge in the 19th century.

German authors during this period wrote ceaselessly. Around 14,000 new publications appeared in a single year in 1843. Measured against population numbers at the time, this reaches nearly today’s level. And although novels were published as well, the majority of the works were academic papers.

The situation in England was very different. “For the period of the Enlightenment and bourgeois emancipation, we see deplorable progress in Great Britain,” Höffner states.

Indeed, only 1,000 new works appeared annually in England at that time — 10 times fewer than in Germany — and this was not without consequences. Höffner believes it was the chronically weak book market that caused England, the colonial power, to fritter away its head start within the span of a century, while the underdeveloped agrarian state of Germany caught up rapidly, becoming an equally developed industrial nation by 1900.

Even more startling is the factor Höffner believes caused this development — in his view, it was none other than copyright law, which was established early in Great Britain, in 1710, that crippled the world of knowledge in the United Kingdom.

Germany, on the other hand, didn’t bother with the concept of copyright for a long time. Prussia, then by far Germany’s biggest state, introduced a copyright law in 1837, but Germany’s continued division into small states meant that it was hardly possible to enforce the law throughout the empire.

OK, this next reference also isn’t peer reviewed, because it is a science fiction courtroom comedy about a galaxy beholden to the human race because of their helpless addiction to catchy pop songs: Reid (2012).

Cultural appropriation is another great talking point generator. For one foray into this weird zone, see Justin E. H. Smith argues that imitation is a sincere form of flattery, also for things that sometimes are claimed to be cultural appropriation. (extended version)

1 Aside: collage artists I enjoy

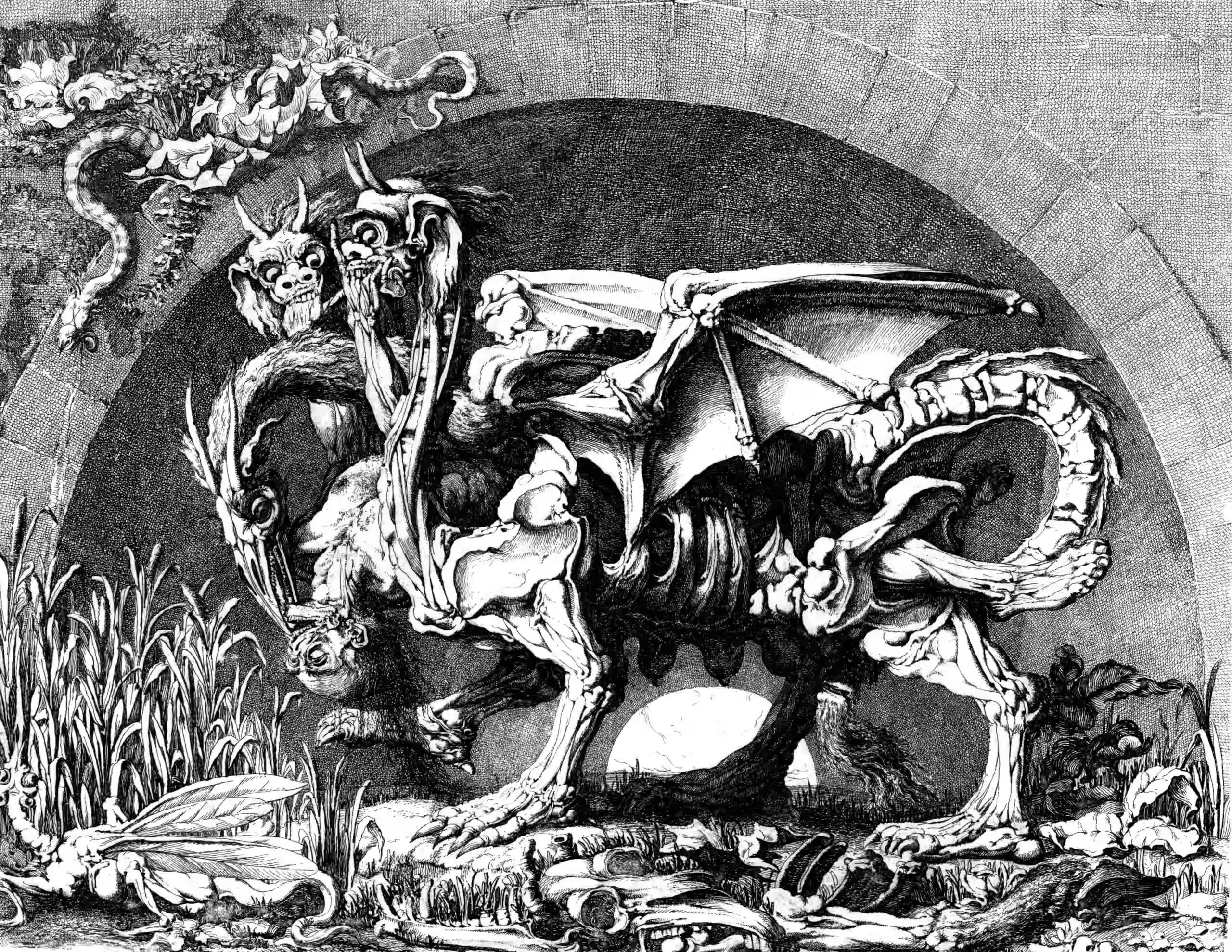

Deborah Kelly and like-minded collage artists.

I quite liked the Victorian State Library’s

#createarthistorychallenge

2 Incoming

Sample Breakdown: The Most Iconic Electronic Music Sample of Every Year (1990-2024)