Historical English

September 23, 2014 — July 8, 2024

Suspiciously similar content

I’m dabbling; My interest in historical linguistics is amateur. But I do find etymology addictive.

The correct medium for a largely oral history is, I suppose, audio. So check out Kevin Stroud’s amateur but expansive History of English podcast.

C&C German.

1 Recreational etymology

I like a fun word origin story as much as the next guy. What of it?

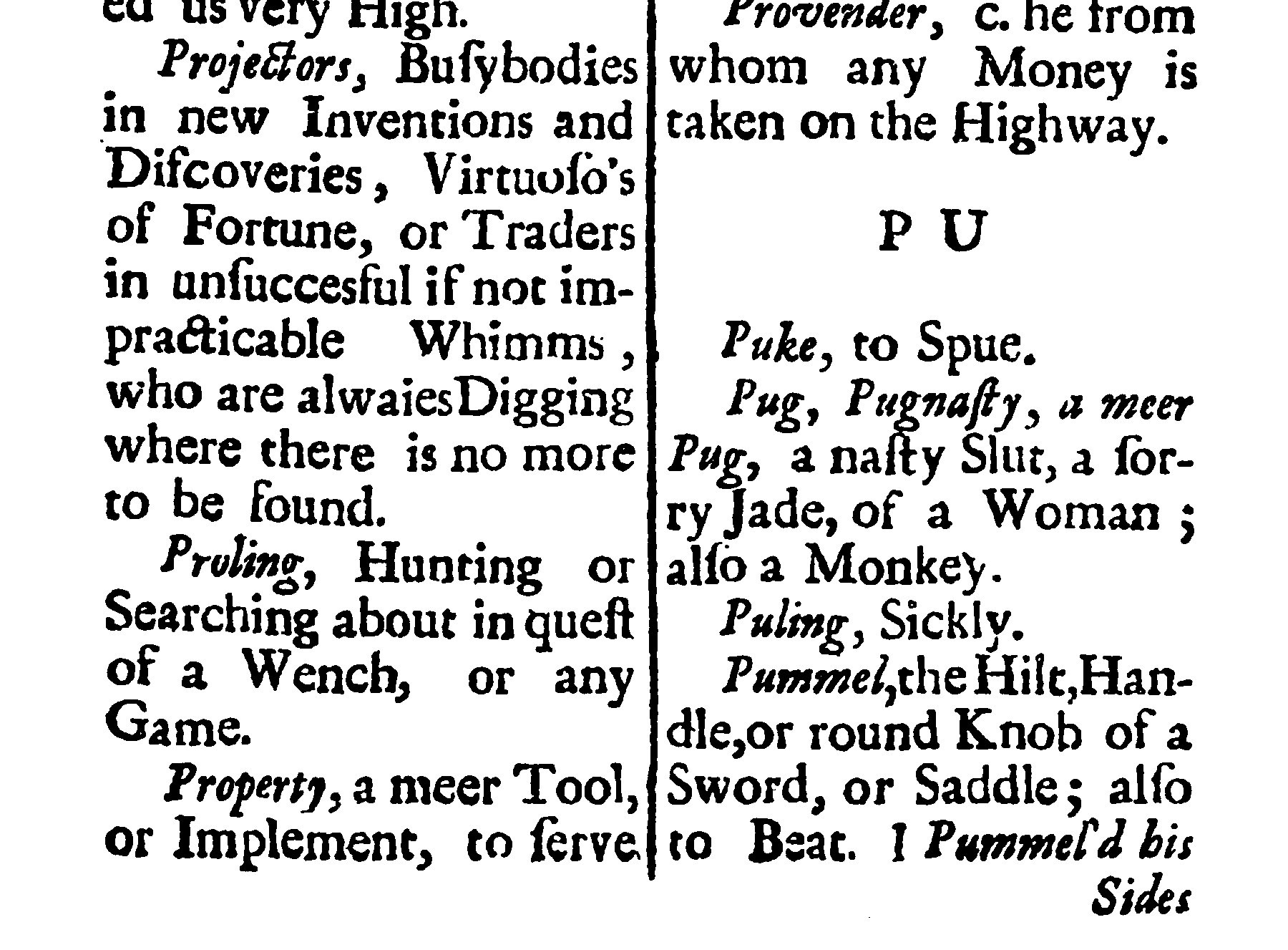

2 Obsolete slang

So 🌶.

-

Green’s Dictionary of Slang is the largest historical dictionary of English slang. Written by Jonathon Green over 17 years from 1993, it reached the printed page in 2010 in a three-volume set containing nearly 100,000 entries supported by over 400,000 citations from c. AD 1000 to the present day. The main focus of the dictionary is the coverage of over 500 years of slang from c. 1500 onwards

A new dictionary of the terms ancient and modern of the canting crew, in its several tribes, of Gypsies, beggers, thieves, cheats, &c., with an addition of some proverbs, phrases, figurative speeches, &c. (E 1899), Originally 1688.

Blackguardiana: or, A Dictionary of Rogues, Bawds, Pimps, Whores, Pickpockets, Shoplifters, Mail-Robbers, Coiners, House-Breakers, Murderers, Pirates, Gipsies, Mountebanks, &c (Caulfield 1793)

Dictionary Of The Vulgar Tongue: A Dictionary Of Buckish Slang, University Wit, And Pickpocket Eloquence. (Grose 1811), originally 1785.

and now considerably altered and enlarged, with the modern changes and improvements, by a member of the whip club. Assisted by Hell-Fire Dick, and James Gordon, esqrs. of Cambridge; and William Soames, esq. of the Hon. Society of Newman’s Hotel.

They are all free online and could greatly season a modern vocabulary. I am not at all sure they are especially real, but we can pretend.

- Belch

- All sorts of beer; that liquor being apt to cause eructation.

3 Pronouncing Middle English

I’d like to read aloud some Chaucer to entertain my Swiss flatmates. This is not trivial; a lot happened to English in the last millennium or so.

Advice:

[…] For instance, some specialists make consonants sound much like consonants in modern English, except clearer, more precise, while other specialists speak consonants as they would in Danish or, God help us, German. For the beginner there’s a valuable lesson in this: Chaucer’s Middle English is relatively easy to fake. What follows here are some notes on how to fake it convincingly, so that one gets pretty clearly the sound of Chaucer’s verse, making people who know the correct pronunciation believe momentarily that perhaps they’ve learned it wrong.

Read aloud or recite with authority, exactly as when speaking Hungarian — if you know no Hungarian — you speak with conviction and easy familiarity. (This, I’m told by Hungarians, is what Hungarians themselves do.) This easy authority, however fake, gets the tone of the language, its warmth and, loosely, outgoing character — not pushy like low-class German, not jaundiced or intimate-but-weary, like modern French, and not, above all, slurred to a mumble, like modern American. Make Middle English open-hearted, like Mark Twain’s jokes…

4 Anglish

Not so much historical as unhistorical, a language based solely on Old English root words instead of all these danged foreign loan words.

The Anglish Wikipedia is occasionally brilliant, covering such worthy topics as The Oned Rikes of America and translating Star Wars. Possibly inspired by the Paul Anderson classic essay on Uncleftish beholding.

For most of its being, mankind did not know what things are made of, but could only guess. With the growth of worldken, we began to learn, and today we have a beholding of stuff and work that watching bears out, both in the workstead and in daily life.

The underlying kinds of stuff are the firststuffs, which link together in sundry ways to give rise to the rest. Formerly we knew of ninety-two firststuffs, from laterstuff, the lightest and barest, to ymirstuff, the heaviest. Now we have made more, such as aegirstuff and helstuff.

The firststuffs have their being as motes called unclefts. These are mightly small; one seedweight of waterstuff holds a tale of them like unto two followed by twenty-two naughts. Most unclefts link together to make what are called bulkbits. Thus, the waterstuff bulkbit bestands of two waterstuff unclefts, the sourstuff bulkbit of two sourstuff unclefts, and so on. […]