Feral

December 2, 2010 — December 2, 2010

Suspiciously similar content

In 2010 I created my first major scene for Rjdj. Rjdj was an awesome app for iPhone, iPad, and Android that made hallucinatory music in interaction with the sounds in your environment and adapted in response to you jiggling and jabbing your phone. A little psychotic break in a box! But it’s now defunct. 😢

That scene was called “Feral”. It was a birthday present for Miriam Lyons. You could download it for free from the Rjdj site.

1 The blurb

Even in your basement office, spores seep in from the outside. Boards warp, microscopic creatures breed in the carpet, and vines strive toward the warmth of your skin. The city evolves too.

In the distance, the mating cry of the automobile, and beneath the pavement, the swamp.

2 How (and why) it works

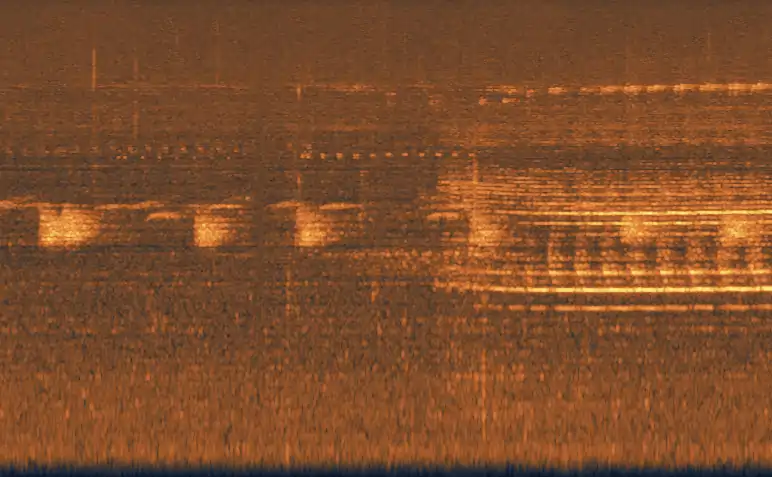

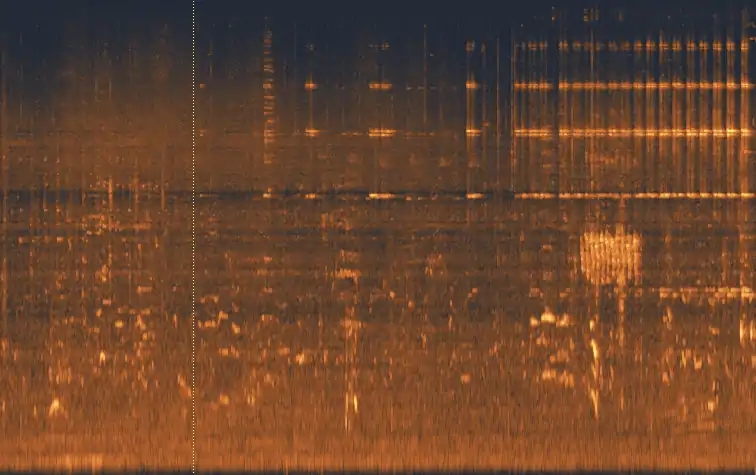

After I came back from the jungle in Malaysia last year, I was amazed by the constant thrum of noise in the jungle. (Radiolab did a cute show about this, by the way.) When I looked at the spectrogram of what was going on there, it was even crazier.

Different creatures — birds, insects, people — colonise different frequencies in the audible spectrum, calling out to each other in warning, mating cries, hunting cries. I couldn’t help comparing it to the radically different soundscapes of the cities I’d been staying in recently — Bandung, Berlin, Sydney, Santa Fe — and the different creatures that filled up the spectrum there. Motorbikes, brakes, fruit vendors. The predators and prey in the urban ecology have such a similar tenor. I wanted to create an experience that would bridge the gap between them.

The simpler part, the background sounds, are basic granular resynthesis of field recordings. I’m pretty proud of the detailed tweaks to make it sound good, but it’s not too complicated a way of generating an endlessly shifting landscape of sounds generated from simple reshuffling of the sounds. A lot of these are from my travels in Southeast Asia, so if there is any secret here, it is that one should carry a decent digital recorder when in the mountains of Java. (If you like the rebab recordings, you can thank the amazing Sundanese multi-instrumentalist Zimbot, whom I recorded in Bandung, West Java. He and I have done other collaborations. Book this guy for a touring show. He’s bloody amazing.)

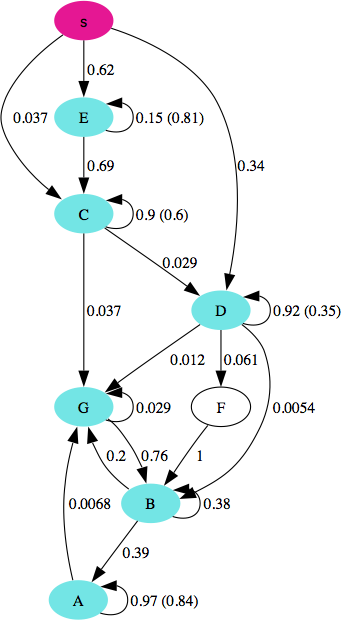

The more complex thing is the “birdsong”. That’s in part real birds, but also cows and bees and people and other things, shuffled using a dynamically-generated Markov chain. This is the subtler and more complicated thing, but I think it’s what makes this work. Markov processes are closely related to Finite State Machines and thus Type-3 languages in the Chomsky hierarchy — the so-called “Regular languages”. This is a family of languages a couple of rungs below what you and I, as humans, speak.

If you browse that Jin and Kozhevnikov article above, you’ll see that they have successfully represented even the most complex birdsong as a Markovian process. This is suggestive of birds having “languages” but of a more pared-back variety than ours. Best of all, it’s a variety of language that’s easy to generate in real time, unlike human conversation. So that is what this app does. When it hears passing birds, or car horns, voices, whistles, whatever, it will record them and then try to respond, by playing a custom Markovian “mating call” straight back, resynthesized and warped a little. Carry it around for a while and you’ll hear people’s voices in the mix too, warbling and stuttering at you, stripped back from human language into something a little more primal.

Predator, prey, or mate?

- Mark Liberman: Finch linguistics